The UG’s collaborationist paper

Mouthpiece for the occupying forces

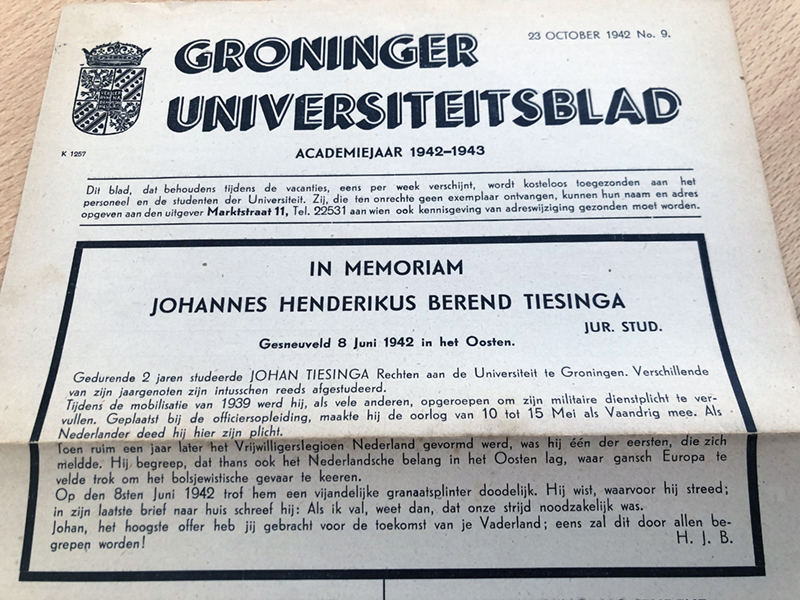

The front page, October 23, 1942. An obituary with a thick black border around it. Johannes Henderikus Berend Tiesinga, a twenty-six-year-old law student at the University of Groningen, died on the eastern front where he was fighting as a soldier in the Dutch Volunteer Legion.

The Groninger Universiteitsblad reports that Tiesinga had fought against the Germans when they’d just invaded the Netherlands in 1940. Nevertheless, he was one of the first to sign up for the legion to fight the ‘communist tyranny’.

He donned a German uniform and travelled to Russia where he was fatally struck by grenade shrapnel on June 8, 1942, more than four months before his obituary was published. While his fellow students were graduating, the Groninger Universiteitsblad wrote, Tiesinga felt ‘that Dutch interests are in the East, where all of Europe was fighting the Bolshevist danger’.

The publication ended the obituary: ‘Johan, you’ve made the greatest sacrifice for your Country’s future; one day, people will understand this!’ Signed: H.J.B. We don’t know who this was, but historians Klaas van Berkel and Annelies Noordhof suspect a friend and fellow student who supported the Germans.

Der Clercke Cronike

The Groninger Universiteitsblad was first published on January 8, 1942, succeeding academic newspaper Der Clercke Cronike, which had been discontinued by its editorial staff, because they didn’t want to become a mouthpiece for the German occupying forces.

You’ve made the greatest sacrifice for your country’s future

Approximately forty-five issues were published. They’ve been preserved in the university archives, but original copies also ended up with the UKrant editors. While Der Clercke Cronike published editorials that were occasionally critical of the establishment, its successor really wasn’t much more than a few pages showing the university’s agenda.

There were notes about staff members moving, information about changes to the pension laws, staff mutations, graduation ceremonies, and when classes were starting again after the spring vacation. There were also a lot of ads, which show just what the war was like: ‘Niemijers Klaroen coffee surrogate, tastes like real coffee.’

Binding agent

The idea behind the Groninger Studentenblad was to provide a ‘binding agent’ for the academic community after Der Clercke Cronike had been discontinued; a showcase for the university, containing practical information. But over the course of 1942, it became a mouthpiece for the German occupying forces, whether by choice or not.

The driving forces behind the publication were rector magnificus Johannes Marie Neele Kapteyn and J.L.H. Cluysenaar, secretary for what’s now the board of directors.

Kapteyn was an out and proud national socialist. He had been appointed rector magnificus by the German occupying forces in September of 1940, against the advice of the Academic Senate. He is believed to be responsible for the deportation of Jewish UG professor Leo Polak, who was murdered in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Secretary Cluysenaar was a different story. Historian Klaas van Berkel, who wrote a book on the history of the UG, paints him as someone who ‘time and again’ compromised to please the occupying forces and who encouraged the academic community not to provoke the Germans.

But unlike his boss Kapteyn, Cluysenaar didn’t subscribe to the Nazis’ ideology: he just wanted to keep the university open, no matter the cost.

Collaboration

According to historian Annelies Noordhof, this was understandable during those first few years of occupation. Forced closure of the university was a constant threat. The universities in Leiden and Delft had been shut down by the German occupying forces in late 1940. The UG stayed open through the end of the war, but it came at a price: a kind of shady type of collaboration.

It appears as though Cluysenaar had initially envisioned the Groninger Universiteitsblad as a real newspaper. Kapteyn didn’t think much of this idea; he feared the same problems that occurred in the final days of Der Clercke Cronike.

Students are now allowed to wear NSB badges and uniforms

The first publication of the Groninger Universiteitsblad, directly after the Christmas holidays in 1942, was entirely without bite. In contrast to Der Clercke Cronike, which required a subscription, the new paper was distributed to anyone connected to the university, for free.

This also solved the problem of the paper shortage. ‘We will no longer be sending cards announcing events like professorial speeches or public classes. They will only be announced in this newspaper.’

Sinister intentions

In late February of 1942, on behalf of secretary general J. van Dam with the then department of Education, Science, and Culture, the paper announced that ‘contrary to earlier regulations, students are now allowed to wear NSB badges and uniforms in UG buildings and on UG property’.

After that, the German occupying forces’ sinister intentions became increasingly clear. Not much later, this same Van Dam said that he’d been told that Dutch universities ‘employed various Jews who don’t have special permission to do so’. The secretary general wanted to know whether ‘that is also the case at this university and if so, to put an end to that as fast as possible’.

The department’s announcement was printed in the Groninger Universiteitsblad in its entirety and repeated by rector Kapteyn, as though he wanted to emphasise its importance. This continued to happen with increasing frequency throughout 1942.

Jews were banned from advertising as tutors in the paper and not much later it was announced that everyone ‘who wears a Star of David’ was no longer allowed to study at the university and was banned from exams. Non-Jewish students, on the other hand, were encouraged to study abroad at a German or Italian university for a few months.

New rector

It’s unclear who decided what was published in the Groninger Universiteitsblad. Was it the publisher? Secretary Cluysenaar? Was it rector Kapteyn who signed off? Or was it his successor after he retired in August of 1942, professor of anatomy and embryology Herman Maximilien de Burlet?

One thing is clear: De Burlet was a more fanatic Nazi than Kapteyn. This became especially clear when he printed a speech to 136 first-year students in its entirety on November 4, 1942.

I would like to inspire you to rebel

De Burlet praised Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini’s leadership, insulted the League of Nations (a precursor to the United Nations), and encouraged his audience: ‘I would like to inspire you to rebel.’

He shook every single first-year student’s hand and gave them a registration card for the university and a copy of Studentenfront, a paper published by the national socialist student organisation of the same name, which had ties to the NSB.

Paper shortage

De Burlet stayed on as rector until April 16, 1945, when Groningen was liberated by the Canadians. He died twelve years later in Königswinter, where he and his German wife had moved after the war. The Netherlands tried to charge him for what he did during the occupation, but Germany refused to cooperate in extraditing him.

De Burlet didn’t benefit from his journalism lapdog for long. Just a few weeks after his speech to the first-years, in November 1942, the Groninger Universiteitsblad was discontinued. The reason was never announced, although it was probably a paper shortage.

The second to last issue admonished the academic community; signs pointing to the air-raid shelters had disappeared from university buildings, probably because students had taken them as collector’s items.

On behalf of the UG, the Groninger Universiteitsblad wrote: ‘I trust this puts an end to the thievery and that the signs will be returned to their proper place.’

Whether this had any effect was never announced.