Liesje prowls fifteen kilometres a day

The adventures of a cat on Zernike

Of course I’d heard it: cat owners should keep their animals inside because they’re eating young birds by the masses. Last year, UG ecologist Chris Smit even pleaded for a test case, because the Nature Conservation Act also forbids cats running loose.

Naturally, this didn’t apply to our cats. They can spot that red one from miles away, if she even leaves the house in the first place. And the other one… Well, that’s Liesje, she’s a pittiful little thing.

Or so we thought.

Liesje, also known as Eeyore, after the gloomy donkey from Winnie de Pooh. Especially when she drags herself through the house, ignoring the bouncy cat toys.

We call her Scrumple, after the girl that makes everything dirty. Because of all the thiks and seed bulbs we pluck out of her fur every day.

And we call her Grey Hunter, from the books about a boy who can move himself through an open field without being seen. Not because of her hunting skills, but because every morning she sneaks through our legs, subsequently to lie snoring on a bed all day.

Gone for days

We never found her, but eventually she would always drag herself back inside

Which was also the reason why sometimes she was gone for days, At least, that’s what we thought. That she would sneak inside somewhere to take a nap and accidentally let herself get locked up. The first few times we still wandered through the neighbourhood calling out affectionately, hoping we would hear her plaintive cry coming from some garage box. We never found her, but eventually she would always drag herself back inside, while we kept wondering where she’d been.

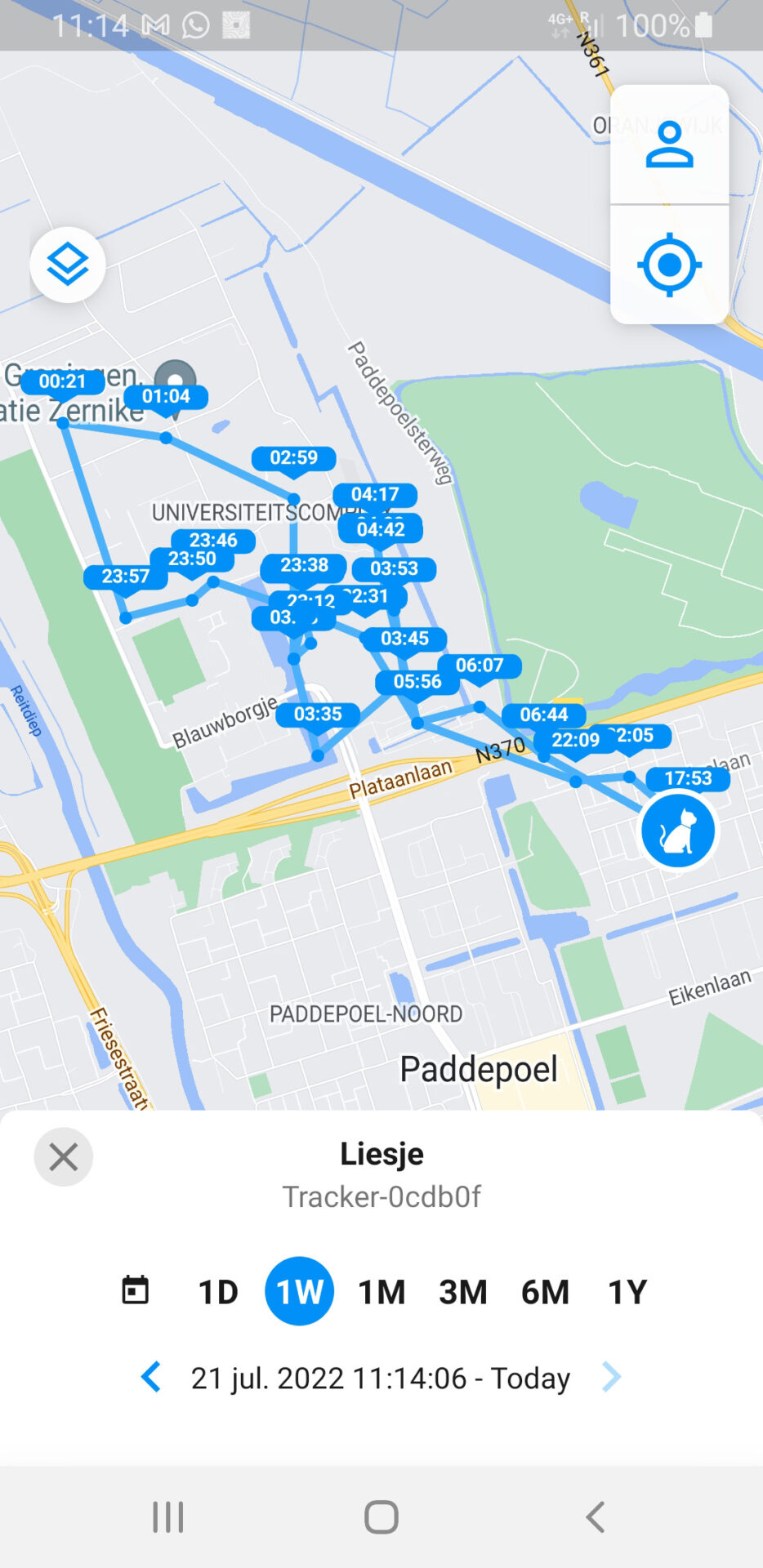

And now we know. Liesje is not inside some garage box, or on some neighbour’s lap; she goes beyond that. Kilometres beyond that, to the university hunting grounds of Zernike.

Summer was still in full swing when we heard that our neighbour wanted to try out his new GPS tracker. He would be babysitting our cats anyway, while we went to Italy for the summer. ‘Isn’t it a little big, for a cat’s neck?’ our kids meowed. But our curiosity was bigger: we wanted to know what she was up to.

‘Suitcase’ around the neck

Days after we left, when after another one of her adventures, she turned up again – our neighbour hung the ‘suitcase’ around her neck. That same night, at our Italian campsite, I watched the first update come in from the app, which checks her location every ten minutes. Liesje was at the Dragant – the former Selwerd III.

Turned out this wasn’t the last time. One time she even spent all day at the student flat. The GPS isn’t super accurate, but from my hammock I had to conclude that Liesje was inside the flat. In an apartment perhaps, or maybe in the communal kitchen, I guessed.

Quite possible, concierge TIebolt Cusiël tells me after I return. According to him, the students would preferably adopt a cat. The latest curious cat half the flat is occupied with, has already gotten a name: ‘Turbo.’ There’s even a bowl and a blanket in the hall for him and their busy discussing him in the group app.

Next morning, the app showed an explosion of blue lines

‘It’s waiting until someone is allergic, or scared, or hates cats’, Cusiël says. ‘So we can’t have it. It’s also in our house rules: pets are not allowed.’ Thank god for that, I thought.

Feringa Building

Meanwhile in my hammock in Italy, my sudoku regularly got paused because I wanted to check where Liesje was hanging around. At the construction site of the Feringa Building, at Nijenborgh 4. At the Zernikelaan, the Duisenberg building, the sports grounds, at Biblionet. Returning books, we jokingly said to each other. Too bad for Lies, it’s midnight, there’s nobody there.

Next morning, the app showed an explosion of blue lines. Liesje turned out to have raced through the entire Zernike complex. Along the Linnaeusborg to the exam hall, another sprint over the construction site to the greenhouses next to Linnaeusborg and eventually, at dawn, back home again via the funeral centre.

That funeral centre turned out to be another popular site. She spent hours near the entrance. Did her gloomy mood lead her to this temple of final goodbyes? Or was she there, lazily chewing on some crispy little mouse?

Taking exams

Waking up the next day, we saw a similar pattern: through the Dragant, the tunnel, to the campus. Sometimes she took a quick exam, dropped by CIT, checked out the construction site and she spent a lot of time at Nijenborgh 4. But also at Linnaeusborg. It looked as if she was walking up the sloping roof there. All the way up to the edge

One time I saw her walking between the animal enclosures behind the Linnaeusborg. With her nose up in the air no doubt, yearning for those fluttering snacks behind the mesh.

Which is very well possible, Martijn Salomons, head of the animal care department says. For people, the grounds are thoroughly closed off with pointy fences and barbwire. But a small animal like a cat can walk in.’ Not in the cages, but on the grounds.

There may also be a buzzard flying over or a stoat passing by that scares the animals

This doesn’t affect the research, Salomons believes. The fact that the animals experience stress makes little difference. ‘These are long-term studies of behaviour or longevity, for example,’ he explains. ‘A cat walking by doesn’t matter.’ There may also be a buzzard flying over or a stoat passing by that scares the animals, he says resignedly. ‘That’s simply the consequence of testing outdoors.’

But the test animals aren’t the only animals on campus. So what else is our nocturnal campus cat, which we even see walking around EnTranCe, up to?

Disturbing suspicion

RUG ecologist Raymond Klaassen has a disturbing suspicion. A few years ago he performed research on cats a little further north, on the other side of the Van Starkenborghkanaal. He fitted cats from the area with transmitters and recorded how they easily wandered a few kilometres from home. “There was no place they couldn’t get to.

He doesn’t know how much they caught exactly, but according to the Bird Conservancy, all Dutch cats combined catch about 18 million preys. ‘I would have loved to have hung a camera on them,’ he says.

‘The numbers are so high that you can expect it to have a population-level effect. Especially in the breeding season, when the little ones have just left the nest and can’t fly yet.’ Then they’re on the ground for a few days. That’s the most dangerous period, with many casualties.’

As a result, he doesn’t think it’s acceptable for people to let their cats run loose during the breeding season. Which is quite a long period: from May to early August.

Following the example of American researcher Pete Mara, Klaassen makes the comparison with dogs: ‘There used to be a lot of problems with dogs biting people. At a certain time people said: this is no longer acceptable; these dogs must be kept behind a fence or on a leash.’ So exactly the same should happen now with cats.

But does that mean we should keep our Grey Hunter home all summer? Then she will get depressed. Can’t we put a bell on her?

Doesn’t help, Klaassen says. After all, cats prowl. When a bird hears the bell, it’s already too late. What might help is a brightly coloured clown’s collar of about 10 centimetres. ‘Birds are very visually oriented.’

Athough it doesn’t help young birds. They remain an easy target for cats. And that’s pitiful too, says Klaassen.