‘Inglourious’ Wijnberg

Quentin Tarantino’s ‘Inglourious Basterds’ is loosely based on a real American espionage mission during World War II.

One of the three secret agents on the mission was Hans Wijnberg, the selfsame Wijnberg who was an organic chemistry professor at the RUG from 1960 to 1987.

The ‘Basterds’ in Tarantino’s film started trouble for the Nazis in France, but Wijnberg and his two fellow soldiers were dropped into Austria to spy on German troop build-up and transportation of supplies in the region.

Eventually, the trio was co-responsible for the relatively non-violent surrender of Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol, to the allies in 1945.

A documentary film about the true story behind ‘Inglourious Basterds’ from 2012, titled ‘The Real Inglorious Bastards’, will be screened on 3 May in Groningen.

There were very few people at the RUG who knew about Wijnberg’s past as a war hero.

According to those at the RUG who knew him best, the former professor and director of the Organic Chemistry Laboratory found it difficult to speak about that period of his life.

Reading time: 10 minutes (1,920 words)

Okay, so maybe they did not actually walk around with bludgeons or Nazi scalps in tow. And no, they did not, in fact, blow up a Parisian cinema, nor did they have the death of Hitler on their conscience. The real ‘Inglourious Basterds’ were not even in France at all: they were dropped in the Austrian Alps, just outside of the Tyrol capital of Innsbruck.

But it is absolutely true that the experiences of Franz Weber, Frederick (‘Freddy’) Mayer and Hans Wijnberg were the model for Tarantino’s movie about a squad of Jewish soldiers fighting under the American flag whose singular goal – ‘killing Nazis’ – eventually brought the entirety of the Nazi leadership and the Third Reich to its knees.

Secret agent

The reality is considerably less preposterous than the fantasies of the famed American filmmaker, but it is no less gripping.

Moreover, 15 years later, one of the three protagonists in the true story, Hans Wijnberg, became a professor and director of the Organic Chemistry Laboratory at the RUG. He saw to it that the laboratory gained international notoriety, especially in the United States where he had lived for 20 years, starting in 1939.

Several months before World War II broke out, his father, Leo Wijnberg – frightened by the anti-Semitic climate and the growing threat of Germany – sent his twin sons Hans and Leo, who were Jewish, away from the Netherlands to the United States. They attended school there and in 1943, Hans enlisted for military service. Within the space of one year, he was trained as a parachutist and a secret agent. In 1944, together with the German-born Mayer, he arrived at the southern European headquarters of the American military’s secret service in the Italian city of Bari.

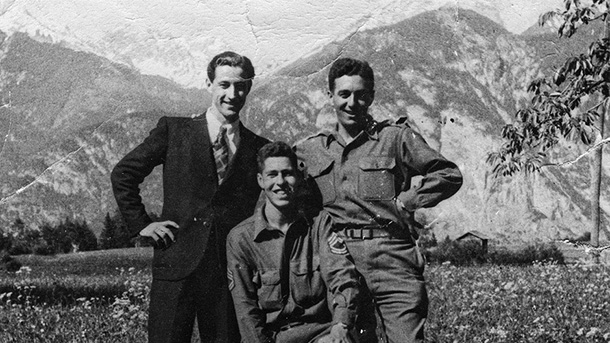

There, the plans were laid for Operation Greenup, and in February 1945, it was go time: Mayer, Weber (a Wehrmacht lieutenant from Austria who had defected) and Wijnberg parachuted from a plane above the Ötztal Alps, landed on a glacier and fought their way through waist-deep snow toward Innsbruck.

From there, they spied on the German train transports in the Brenner Pass, the troop build up in the region and even the production of Messerschmitt fighter planes. Weber provided local contacts, Mayer conducted surveillance and Wijnberg transmitted the intelligence from the loft of a nearby barn back to headquarters in Bari. ‘It worked!’, Wijnberg said of the operation years later. ‘The radio signal bounced across the Alps and eventually made it to Bari, Italy. Unbelievable!’

‘Je ne sais pas’

The trio remained out of enemy hands for a few months, but in the second half of April, Mayer was betrayed by someone who took him to be a high-ranking American officer. The Germans captured and tortured him in the hopes that he would give up his cover. But the spy, claiming to be a French electrician, only gave his tormentors one answer: ‘Je ne sais pas.’

As the allies continued their advance, Mayer narrowly escaped being tortured to death, initially thanks to a German military doctor with whom Mayer maintained a friendship after the war, and subsequently thanks to Franz Hofer, the highest ranking Nazi in Tyrol. He saw the supposed big shot officer as his last chance to escape a criminal tribunal.

When the allies eventually reached the proverbial gates of Innsbruck, Hofer surrendered himself to Mayer in exchange for immunity. ‘I was absolutely not authorised to do that’, Mayer later recalled. ‘But it sounded like a good deal to me.’ And so, the American-German spy greeted the arriving American troops, waving the white flag of surrender and handing over the most powerful Nazi in Innsbruck.

The real ‘Basterds’

The story seems to lend itself easily to the silver screen, even without Tarantino’s unbridled imagination. And the story was eventually presented in film form, but only in 2012. It was not made into a feature film, but rather a documentary which cleverly capitalises on Tarantino’s blockbuster hit, as the title ‘The Real Inglorious Bastards’ attests.

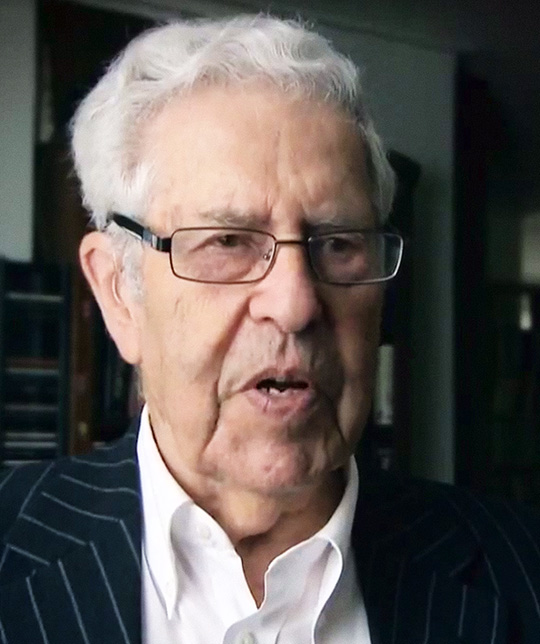

In the documentary, Wijnberg and Mayer (Weber passed away in 2001) revealed the true story. For Wijnberg, it was the last time he would speak of his experiences: the day after the interview – on May 25, 2011 – the 88-year-old professor emeritus died due to complications from heart problems.

Bicycle tire glue

Hans Wijnberg’s interest in chemistry may have been genetic. His grandfather Louis invented the ‘Simson solution’, a glue that is included in bicycle tire repair sets of the same name. The family business was passed on to Hans’ father Leo, and shortly after the war ended, Hans and Leo sold it. Hans Wijnberg said in a radio interview in 1998 that he was proud that his grandfather’s business still existed. For Wijnberg’s protégé Ben Feringa, the bicycle tire glue is a fine souvenir to remember his mentor: ‘Whenever I buy a tube of Simson, I think of him.’

While the documentary has already been aired on The History Channel several times, the film will have its Groningen debut in the synagogue on the Folkingestraat on 3 May. The timing is fitting, and not only in light of Remembrance Day and Liberation Day. On 15 April, Mayer, the last surviving member of the real ‘Basterds’ trio, passed away. Frederick Mayer was one of Wijnberg’s biggest role models. ‘He always spoke about Freddy with such pride’, says professor Ben Feringa, who was a PhD candidate of Wijnberg’s once upon a time, of his old mentor.

Academic father at the RUG

He calls Wijnberg his ‘academic father’. ‘I have so much to thank him for. He was a fascinating and exceptionally inspirational man’, according to Feringa, who praised his former teacher in an obituary in 2011. Although Feringa and Wijnberg had a close professional relationship, it was only after Wijnberg entered retirement that he inducted his pupil into the club of those who knew about his experiences during the war. ‘He didn’t speak very much about it before, it only really came out in his final years’, Feringa says.

That seems to be something of a pattern among Wijnberg’s RUG colleagues. Jan Engberts, who has been a professor of organic chemistry since 1978, also recalls that Wijnberg never made a big deal of his military history. ‘I can’t really remember him ever bringing it up at work’, says Engberts. ‘But Hans was also very selective about whom he told.’

Even at the UK, where Wijnberg was a columnist for years, no one seemed to be aware of Wijnberg’s role in World War II. ‘As far as I know, it was virtually unknown at the UK’, says Luuk Hajema, editor-in-chief of the newspaper – which was still on paper and was called Universiteitskrant back then – until 1989. ‘In the five years that I was there, I cannot remember it ever being discussed.’

Biography

Hajema is currently working on a biography about the ‘Inglourious Basterd’ of yesteryear. Through conversations with Wijnberg’s family members, friends, acquaintances and colleagues, he has come to know a bit more about his activities toward the end of World War II and how he talked about that time.

‘It wasn’t totally taboo’, Hajema says. ‘There was an inner circle of people who were aware of it, but he certainly wasn’t flaunting it. His son Anthony also told me that in their home, Wijnberg kept quiet about the war for a long time. The subject was broached later on, but he never, ever spoke about his feelings. That was really taboo.’

See the movie?

On Tuesday, 3 May, ‘The Real Inglorious Bastards’ will be screened in the synagogue at Folkingestraat 60. The screening will begin at 20:00 and will include a preshow consisting of historic footage of Hans and Loek Wijnberg’s departure for New York in 1939. The entrance fee is five euros.

More information is available at the synagogue’s website.

An in-depth radio interview in 1998 where Wijnberg tells his life story seems to confirm that assessment. In this episode of ‘Een leven lang’ (‘Lifelong’) (which is available online (audio in Dutch)), he speaks at length about their adventures in Tyrol. But when the interviewer tries to probe a bit deeper about Wijnberg’s emotions when he talks about his memories of his parents and his younger brother, all three of whom died at Auschwitz, he tersely says that he does not want to talk about it.

Regret

That sounds pretty typical of the person that Wijnberg was, according to his old friends and acquaintances at the RUG. Wijnberg was proud and prone to bragging every now and again, Engberts says. And that pride seemed to be at odds with a sense of shame that some of those close to him observed when he thought back on the persecution of the Jews in Europe and especially the deaths of his family members.

‘He said to me once that he had a sense of regret about going to America in 1939’, Engberts says. ‘’I should have stayed here to help the Jews’, he used to say.’

That is an alternative that Feringa cannot imagine. ‘When I watched ‘The Real Inglorious Bastards’, I actually realised how differently everything could have turned out. By the same token, I may not have had Wijnberg as my supervisor. If that had happened, would I have even become a professor? You just never know!’

‘Kill Wijnberg’

After the war, Wijnberg briefly returned to the Netherlands to try to find out what had become of his family members who stayed behind. But the Red Cross was the bearer of tragic news: his parents and his younger brother Robbie died at Auschwitz. Wijnberg decided to resume his life in the United States.

There, he graduated with a degree in chemistry and went on to work as a researcher at several American universities, only to eventually wind up back in the Netherlands again in 1959 thanks to a fellowship that brought him first to Leiden. Starting in 1960 onward, he served as a professor and director of the Organic Chemistry Laboratory at the RUG.

Having lived in America for roughly 20 years, Wijnberg had a thick American accent when he first repatriated, RUG professor of organic chemistry Jan Engberts recalls. But that was not the only manner in which Wijnberg brought a ‘strongly American atmosphere’ along with him. ‘He was more approachable than what was considered normal at that time in the Netherlands, and he was constantly promoting the lab. That really raised our profile abroad, especially in the U.S.’

Wijnberg had a penchant for stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry that focuses on the spatial arrangement of atoms, molecular symmetry and the consequences of that on how materials react to one another. But he was not eager to teach, Engberts says. ‘If he was supposed to give a lecture, he would always try to pawn it off on someone else.’

Be that as it may, Ben Feringa remembers his former supervisor as a good mentor. ‘People really learned a lot from him’, he says. ‘But he was not an easy man.’ Engberts can attest to that, too: ‘He was great with the people who worked closely with him on a daily basis, but with everyone else, he varied between mild-mannered and straight up annoying.’

‘With such a defiant attitude, he was often at odds with people’, Wijnberg’s biographer, Luuk Hajema, confirms. Wijnberg, who was quite conservative by Dutch standards, was strongly opinionated, but his point-of-view was rarely in keeping with the prevailing leftist spirit of the University Council in those days, where he also made himself heard.

Moreover, Wijnberg had a healthy American hatred of communism. That position in particular led to a regular butting of heads, both in the University Council and at the Universiteitskrant, where Wijnberg wrote headstrong columns under the title ‘From the other side’ (‘Van de andere kant’). He had a notable falling out with the Groningen Student Union (Groninger Studentenbond) in the early ‘80s, and there were even several walls defaced with the slogan ‘Kill Wijnberg’. But it is unlikely that Wijnberg lost any sleep over that. ‘That man wasn’t afraid of anything.’