Transferable trauma

Stressed mum, depressed kid?

When she was a young adult, Mayerli Prado Rivera was worried about her mental health. Several women in her family were suffering from psychological problems. What if that was her future, as well? And why were these issues so prominent in her family?

It’s the reason she decided to study psychology, which ultimately made her fall in love with neuroscience. ‘I thought it was amazing how it could teach us to better understand the biology of mental health.’

The PhD student has spent the past fifteen years studying stress. She’s recently started to focus specifically on stress in women. She’s trying to find out whether sustained stress in female rats increases the chance of depression in their young. ‘I hope this will give us more insight into whether this happens in people as well’, says Prado Rivera.

To achieve this, she compares the behaviour of rats with stressed-out mothers with that of rats whose mothers lead a low-stress lifestyle. Before, during, and after their pregnancies, she exposes female rats to stress at random intervals. She puts them in smaller cages, forgoes feeding them for a while, or, after they’ve been born, separates the young from their mother for a while.

Behavioural tests

Once the young reach maturity, she performs various behavioural tests to see whether or not they’re depressed. ‘Depressed rats, for instance, tend to isolate themselves from other rats’, she says.

Depressed rats tend to isolate themselves

She also studies the differences between rats with a genetic predisposition towards depression and those without. Earlier studies have shown that a combination of environmental factors and genetics can impact the chance of depression. ‘I count the mother’s stress as an environmental factor.’

Prado Rivera expects this will lead to depressive behaviour in the young, and that the males will experience the effect more severely. ‘They are more prone to stress than females’, she says. Studies have shown, for instance, that males tend to show less social behaviour and more aggression.

Effect in people

She hopes her work will give her insight into the relationship between long-term stress and depression in people. ‘Human beings and rats are alike in many ways’, she emphasises. ‘We are both social animals that utilise communication.’

Obviously, she is also aware of the differences. ‘You can simply ask people how they’re feeling, while you can never know what goes on in a rat’s mind’, she says. ‘While we are able to interpret rats’ behaviour, we’ll always do so from a human perspective, which means there is the potential for biases.’

Nevertheless, her research could open doors to new insights and perhaps even to medication that could help alleviate symptoms caused by stress, she thinks. ‘If it turns out that prolonged exposure to stress leads to anxiety in people, we know that we have to tackle those symptoms first.’

Conscious choices

But wouldn’t such research also potentially lead to mothers being blamed for their children’s depression?

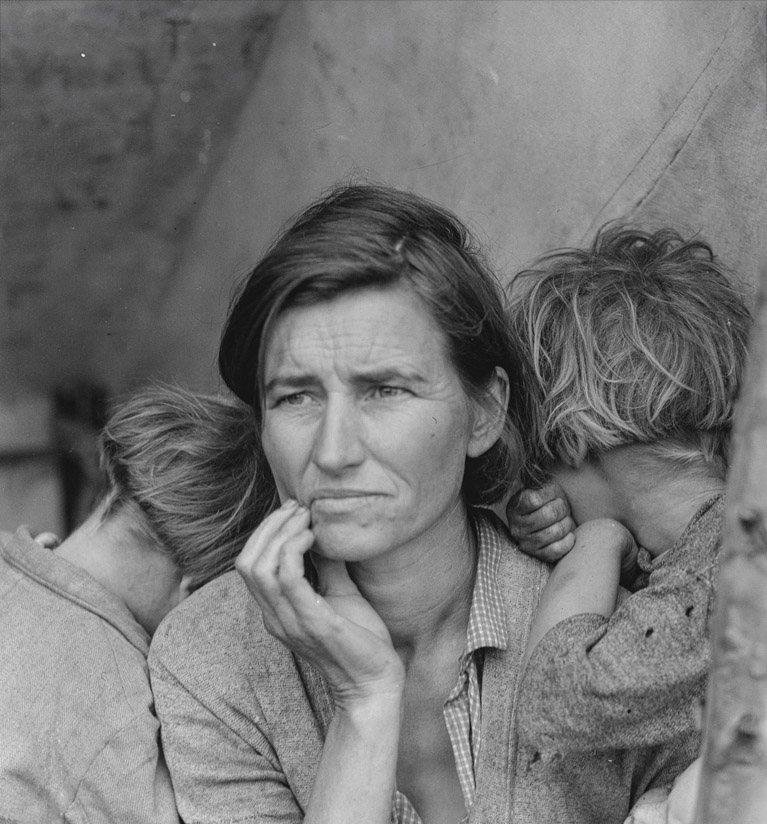

Intense stress impacts the way mothers take care of their children

Prado Rivera has to think for a second. ‘Your question reminds me of studies on autism in the twentieth century. They claimed that autism was caused by the way children were raised, which made parents feel guilty.’ It was later discovered that there was a genetic component in autism. ‘Even if children had the sweetest, most caring parents, they still developed these mental conditions.’

Instead, she hopes her research will help parents make more conscious choices. ‘Perhaps it will make them realise how stress from overworking can impact their children’s health.’

More support

More awareness of this phenomenon, including from politicians, is incredibly important, she says, because this kind of stress can impact multiple generations. ‘The consequences are devastating, truly devastating. Intense stress impacts the way mothers take care of their children. And that will most likely affect the way those children raise their children down the line.’

Fortunately, she says, awareness of support for mothers is growing, including in her home country of Colombia. ‘Many years ago, women in Colombia had to go back to work very quickly after giving birth. In 1990, mothers got twelve weeks of paid parental leave. The law recently changed, allowing mothers to stay with their newborns for an extra month.’ That means they experience less stress.

Research like hers can provide support for people having a hard time, Prado Rivera thinks, and can contribute to less stress while raising children. ‘I think it’s important to be open and honest about mental health. We can learn from other people. Even if you are under a lot of stress, your life will be much easier if you’ve got really good friends, a partner, family, or colleagues.’