It’s a shame it’s just sitting there empty

Homeless or squatting

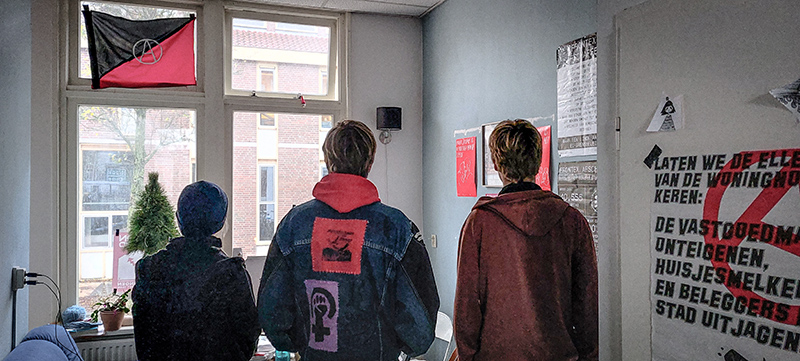

Red anarchist flags bearing a large black ‘A’ on them are everywhere throughout the house, accompanied by posters announcing protests and demonstrations against the housing crises in Groningen and Rotterdam. Also hanging on the wall are the banners used during the protests: ‘If vacancy is a right, squatting is a necessity’, for example, and: ‘Squat all day, squat all night. Housing is a human right.’

We’re in the building at Zuiderkuipen 18 and 18a, a large town house that the seven students have been squatting in since November 12. The building had been empty for months and the students were homeless.

Duct tape

There’s a smell of marijuana and tobacco in the air. There are mattresses on the floor in several of the bedrooms. The locks on the doors have been replaced, and only the squatters have the keys. ‘We don’t want to drill into the walls’, says Maria Walther, student of international relations and international organisations. ‘We don’t want to cause any damage.’ They even used duct tape to attach the fire alarms to the ceiling.

Maria is part of a group of students who mostly met each other during the occupation of the Academy building. Maria spent a long time trying to find a room, but after sending three hundred messages, she’d only been invited to four viewings. Now that she’s living at Zuiderkuipen, she doesn’t want to leave. ‘It’s such a beautiful house, it’s a shame that it’s just sitting here empty.’

A big group of students slept in a barn and a few caravans

Paul Schwarz, squatter

She and her fellow squatters had known for a while that the house had been empty. No one was doing any renovations. They could no longer watch the building waste away in front of their eyes. They were also increasingly frustrated at not being able to find a room to live in.

Realistic

‘It was the most realistic way I was going to find a place to live’, says German student of spatial planning and design Paul Schwarz. He, too, has been affected by the housing shortage. He has been responding to at least ten rooms a day since May, but he’s only been invited to a single viewing.

Paul was forced to sleep on the couch in the shared living room of emergency housing the first few weeks after he’d come to the Netherlands. He even had to pay a hundred euros a week for that.

In October and November, he found a place to stay at a farm in Assen. ‘A big group of students slept in a barn and a few caravans.’ But the cold and the distance to the city made the situation untenable. ‘They haven’t even returned my security deposit of 150 euros’, he says. ‘There were loads of fishy things going on there.’

Public

But having a roof over their heads isn’t the only reason the students decided to squat in the building. It’s also their way of saying that they’ve had enough of the housing crisis. ‘After the protest on the housing crisis on November 28, we decided to take our movement public’, says Maria.

It’d be selfish to not help people with the same problems as us

Maria Walther, squatter

They created an Instagram account to spread their message. But they also wanted to be a community for homeless students. ‘It’d be selfish to not help people with the same problems as us’, says Maria.

And they do. They provide people a place to study, free dinner, or a hot drink. ‘No one leaves here hungry.’

Thumbs up

The neighbourhood loves the students. Neighbours have donated sheets, furniture, and even croissants, says Maria. People also regularly give a thumbs up to the people in the living room when they pass the house. ‘All the responses have been really positive, which is nice’, says Paul.

However, not everyone is happy with the squatters. The building is owned by housing corporation Patrimonium, which manages approximately 6,700 houses across Groningen. The corporation would prefer it if the squatters left immediately. ‘The building simply isn’t suitable to be lived in’, says director Bas Krajenbrink.

‘Investments are needed to ensure it meets the requirements for rental’, he says. According to him, there are issues with damp and fungus in the basement, and there are structural issues that affect the balcony. ‘It’s not safe to rent out the property, or we would have.’

Leave

Patrimonium wants to start renovating the house in January in preparation of putting it back on the rental market. That means the students will have to leave. ‘They’re okay with that’, says Krajenbrink.

Ultimately, it’s their own responsibility to find a place to live

Bas Krajenbrink, director of Patrimonium

But the corporation wants the students to leave now. The squatters are less okay with that. ‘We’re worried that they’ll be kicking us out of our house in the winter’, says Maria.

So far, the parties haven’t succeeded in finding a solution that pleases them both. ‘Patrimonium made us a ridiculous offer’, the squatters said in a press release. ‘They offered us a different place to live for a normal price if we showed them our IDs. As far as the location, state, or even the existence of these houses, we’re supposed to just trust them, since they’re a “social” housing corporation.’

Summary proceedings

Last week, Patrimonium decided to start summary proceedings to make sure their contractors can start work in January.

‘In the end, what matters is that the squatters leave’, says Krajenbrink. ‘If they happen to do so voluntarily before January it would be great, but if they don’t, we have to make sure the property is empty so the contractors can start. Ultimately, it’s their responsibility to find a place to live.’

The squatter won’t leave until they have proof that the renovations will be taking place. When push comes to shove, they don’t trust the housing corporation one bit. If they do have to leave the property, that doesn’t mean the end of their squatting careers, says Maria. ‘There are plenty of other empty houses in the city.’