Landlords’ dirty tricks

Bullied to make bank

There she is, dressed in nothing but a towel, facing a strange man. Merel (24) just got out of the shower; her hair is still wet. He’s breaking in, she thinks. ‘What are you doing in my house?’ she asks him. ‘Key!’ the man yells in broken English. ‘Key, key!’ She doesn’t know where he got a key.

Panicking, she calls her new landlord, but he’s not picking up. She decides to call the police. Not much later, her landlord calls back: what on earth made her think it was a good idea to call the police? The man has a key; surely it’s obvious that he’s a new tenant.

Lucrative

Merel’s is not an isolated case. In the Indische Buurt, Linda suddenly finds herself sharing a house with two Slovakian migrant labourers. Every week, the hallway reeks of their weed. In the Korrewegwijk, Sofie suddenly has a Polish man for a roommate, and in Paddepoel, ex-prisoners move into Suzanne’s house. Talking to the landlord does nothing.

What on earth made her call the police?

Being harassed by your landlord who puts homeless people, unsavoury people, and other non-students in your house; there are no official numbers, but after asking, it turns out it happens quite often to students in Groningen.

Why? Money. Student rooms don’t bring in much money; luxury apartments are much more lucrative. But you can’t just evict students, as they’re protected by law. Landlords therefore have to resort to other tactics. Their solutions have been effective; almost every student that UKrant spoke to has moved since drug-addicted, drinking, and partying men moved into their all-girls houses.

Parties

After that first man, more come into Merel’s house. The original new roommate starts bringing home friends. At some point, at least ten men have a key to the house. They regularly have parties that last for days. They go through immense amounts of weed and coke. There’s a little white car parked in front of the house that the men keep getting nitrous oxide tanks from.

One day, as she’s doing the dishes, it happens. Merel is dipping her hands into the soapy water when she hears the door to the room next to her creak open. One of the men staggers inside, high as a kite, his eyes bloodshot and staring at nothing.

Merel holds up her washing-up brush like a weapon. ‘Don’t come any closer!’ she warns, waving the brush about. Soapy water goes everywhere. For a few seconds, the man stands perfectly still. He’s going to attack me, Merel thinks. Her heart is beating so fast. But then the man abruptly leaves the kitchen, walking backwards. He locks the door to the room.

Five minutes later, the whole situation repeats. The door opens, the man comes out, stares for a while, leaves walking backwards, and locks the door. The incident has made Merel afraid to go to the bathroom. What if the men are wandering around the house just as she’s leaving her room? She makes sure to always keep her door locked.

Destroyed furniture

Numerous phone calls to the police don’t do anything, and the landlord pretends nothing is going on. He does tell them of his plans to turn the student house into luxury apartments. But because of their contracts, he can’t just kick the students out. So what he’s doing, Merel has realised, is slowly make the house at the Nieuwe Ebbingestraat a nightmare to live in, in the hopes the students will leave on their own.

Merel is afraid to go to the bathroom

But it looks like Merel and her roommates aren’t leaving fast enough according to the landlord. When they come back from a holiday, the entire upstairs of the house has been destroyed. There’s nothing left in one piece, including their furniture. Livid, they call the owner. He says he assumed the students didn’t live there anymore and had left the property; in reality, they hadn’t even cancelled their rental contracts.

The renovations have since finished. Before, the house had seven student rooms, which each cost 250 euros in rent. Today, it has five apartments that net the landlord at least 4,000 euros a month.

Urine everywhere

At Suzanne’s house in Paddepoel, strange men keep coming and going. One of them, a former prisoner, tells Suzanne he moved in at the request of the landlord. He says the landlord also asked him to cause a disturbance now and then, in the hopes the students would move out as quickly as possible.

There are more incidents between the tenants and the owner. After a noise complaint, the owner suddenly appears at the door, and proceeds to urinate in several places in the house, which continues to smell for days. Suzanne had already taken to sleeping with a knife under her pillow because she was so scared. After this particular incident, she’s fed up; she leaves the house for good the next day.

In situations like this, students are often powerless. Utrecht professor Ton Jongbloed, who specialises in rent law, says students don’t have a leg to stand on when strange men are suddenly moved into their house. ‘Landlords can decide who they rent to. It’s difficult to prove that their doing something maliciously’, he says. ‘Tenants can try to go to court, but it’s unlikely they’ll win.’

Hotline

The Woonbond, an organisation that protects the interests of tenants and house hunters, is aware of the practice and hopes the Good Landlordship Act, which went into effect in July of 2023, will eventually put an end to situations such as these.

It’s difficult to prove that landlords are being malicious

‘Tenants’ most important tool is the hotline in their city. When push comes to shove, the city could take away someone’s renter’s permit’, says a spokesperson for the Woonbond.

However, the chances of that happening are slim, and it doesn’t solve the actual problem. Renter’s permits are issued to properties, not individuals. Even if a malicious landlord loses his permit for one property, he can continue bullying tenants elsewhere.

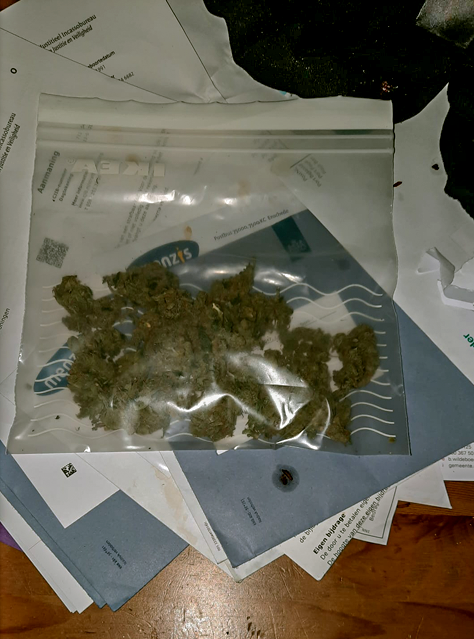

Mountains of weed

Merel and her roommates have since left the house at the Nieuwe Ebbinge behind. During one of her last days in the house, she finds dozens of baggies of weed in the kitchen cabinets, badly hidden in dishes and pans. She finds more in a stack of shoe boxes in a corner of the kitchen.

She comes to the realisation that the landlord managed it after all: he harassed her until she left. But in the end, what matters most is her own safety.

For privacy reasons, the names Merel, Suzanne, and Linda are pseudonyms. The editorial team knows the women’s real names.