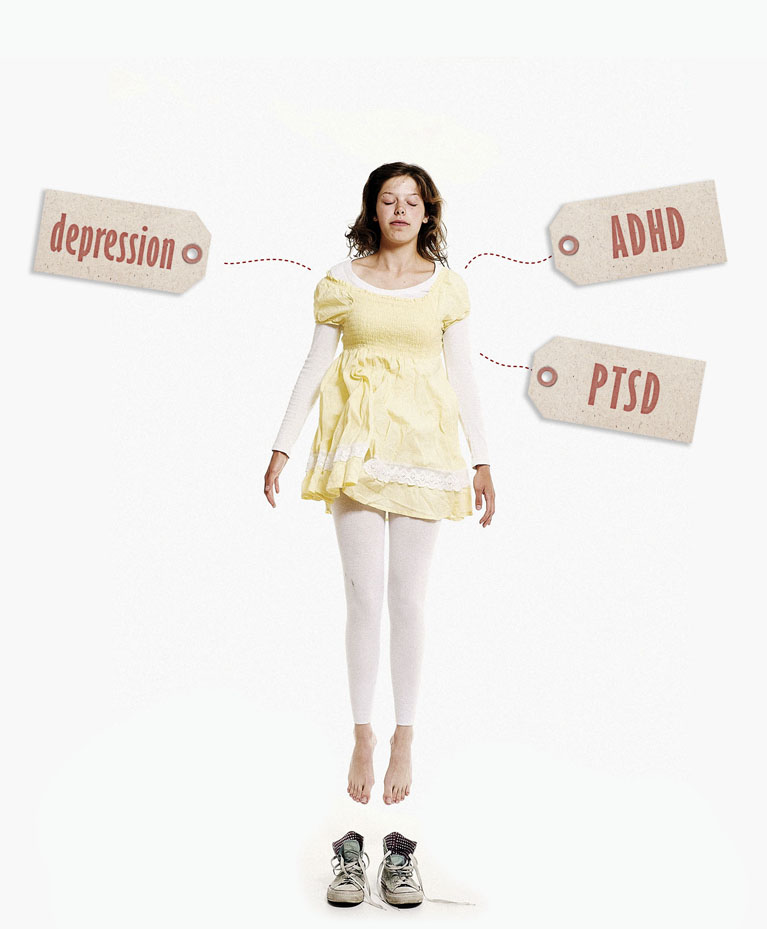

There’s relief, but also a stigma

Labels are hard to get rid of

‘When I haven’t cleaned my room, I’m like, it’s because of my ADHD. I’ll just leave the mess. It’s an explanation, but I also use it as an excuse.’

Johanna Rietveld (20), a second-year psychology student, is certainly familiar with the DSM-5, the handbook that classifies psychological disorders. No fewer than four of them apply to her: in addition to her ADHD, she was diagnosed with PTSD, depression, and a generalised anxiety disorder.

Johanna is far from the only student diagnosed with a psychological condition. According to the Trimbos Institute, 43.7 percent of students were diagnosed in 2022. In 2007, that number was at 22.4 percent. Among the different types of groups – working people, retirees, stay-at-home mum or dad – the increase among students is the highest. Only the unemployed are diagnosed with a psychological condition more often (48 percent), but that number was already at 36.7 percent in 2007.

Affirmation

The wait periods at student psychologists keep getting longer – the Trimbos Institute speculates it’s because of the pressure to perform and social worries – which also means an increasing number of students are getting an official diagnosis. But does getting that label from a professional actually benefit people?

I didn’t like getting labelled like that, but it was kind of a relief

For Johanna, being diagnosed with ADHD felt like an affirmation. However, she struggled with the PTSD diagnosis. ‘It just felt a little weird to me. I thought that was only for people who’d been in a war or something. I didn’t really feel traumatised enough to earn the label.’

People may develop post-traumatic stress disorder when they’ve experienced something scary or shocking that they don’t process properly. They start to experience symptoms such as flashbacks or nightmares, and this can impact their normal way of functioning. As Johanna’s therapist told her, a traumatic experience can range from war to an accident, loss of a loved one or, in Johanna’s case, sexual violence.

‘I didn’t like getting labelled like that, but it did help me understand things. In that sense, it was kind of a relief’, she says. ‘I’m not crazy or sick in the head, there’s actually something wrong. Now I can rearrange my life to deal with it, or start treatment.’

Acceptance

Second-year student of notarial law Marijke (19) was diagnosed with depression. ‘It didn’t really come as a surprise. I couldn’t even get out of bed, so it was an obvious conclusion.’ However, she also got the diagnosis PTSD, which she, too, associated mainly with war trauma. ‘I had a hard time getting to grips with that.’

I’m now able to better explain not just myself, but my feelings and reactions

However, she realised the symptoms did apply to her. ‘I get these spasms and I completely shut down when I’m overstimulated – that’s all part of PTSD. I never would have been able to recognise that symptom in people before.’

She says the diagnosis really helped her. ‘I’m now able to better explain not just myself, but my feelings and reactions. Now, whenever I panic because someone’s touching me, I understand why. This also helps me explain it better.’ It’s also helping her recover: ‘I’ve been able to accept it better, and I’m learning how to deal with particular situations and matters.’

Stigma

Clinical psychology professor Marieke Pijnenborg points to another important function the DSM-5 and its corresponding psychological labels have: ‘In the current healthcare system, you need a diagnosis to qualify for treatment. That’s just how the system works.

She herself is not necessarily a fan. ‘These labels don’t say anything about the progression of the condition or its causes’, she says, but once diagnosed, it’s almost impossible for people to get rid of them. ‘These aren’t like regular diseases that can be cured. There’s no form of “de-labelling”: it’s not like you can be in remission, like with cancer.’

There’s no form of ‘de-labelling’: it’s not like you can be in remission

That’s a potential problem, since these kinds of labels come with quite a bit of stigma. Pijnenborg realised this when she was treating patients for schizophrenia. ‘There’s this idea that people like that are dangerous and can’t be trusted. That can be really demoralising.’

Pijnenborg emphasises that caution is recommended. ‘It’s important to really inform your patients what a diagnosis entails.’ However, there are advantages, she admits. ‘Not only can a diagnosis lead to support and understanding, but it also creates a common language to communicate with both patients and colleagues.’

Leftist bubble

Marijke decided to be open to her fellow students and crew mates about her depression. ‘That’s a label that students know how to deal with’, she says. However, she told almost no one that she also had PTSD; she was worried about how they’d react. ‘People immediately want to know what happened, but when you’re suffering from PTSD, that’s not something you necessarily want to explain.’

In an effort to break taboos concerning psychological disorders, she did write a few posts about mental health on social media. But she limits that honesty to her direct social circles. ‘I exist in a fairly leftist bubble, where there’s no stigma on labels and people react fairly favourably. But I stopped talking about it with people over thirty or forty who don’t work in healthcare.’

Not taken seriously

After a bad experience, Johanna has become more reticent in talking about her diagnoses. ‘It’s hard to be open to people who don’t know much about it, or people who are prejudiced. They’re quick to think that I’m crazy. I don’t need that kind of stigmatisation.’

She once attended a party at someone’s house where she became over-stimulated because of the music and people around her chatting. ‘I asked if the music could be turned down. A friend of mine responded really rudely: she said she didn’t want to make any adjustments because of my ADHD. It was really hurtful. It felt like she didn’t take me seriously at all.’

But Johanna is learning how to cope with her labels. That’s in part because of her family, she says. ‘Pretty much everyone in my family has their own diagnosis, apart from my dad. My mother is a lot like me and my brother is autistic. And to be honest, some things from the DSM apply to my dad as well.’