A deep dive into the Dead Sea Scrolls

The man who wrote the Bible

What should we call him? ‘Baruch’, says Gemma Hayes. ‘Ba for short.’ He was one of the scribes of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

That name, a reference to the secretary of prophet Jeremiah, is meant for herself. For her research at the Qumran Institute in Groningen, in absence of a real name, he was given the reference GQS001 (Groningen Qumran Scribe number 001). The number offers space for other, yet to be identified, scribes.

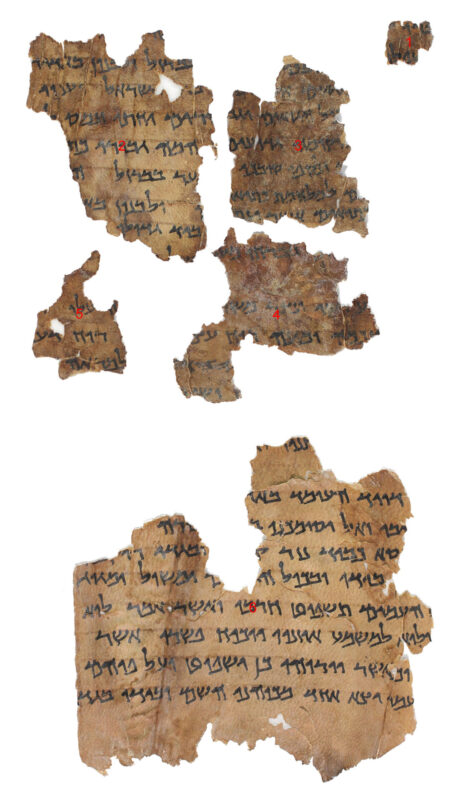

As one of just a few, GQS001 – Baruch – wrote more than one of the scrolls of parchment, papyrus and copper that were found in eleven caves near the Dead Sea. Eight of them, Hayes established conclusively with a special combination of the ancient-old art of palaeography and artificial intelligence. Last week, she received her PhD for her research on his handwriting.

Oldest known biblical texts

In the caves near the remains of the settlement of Qumran, just south of Jericho in today’s Israel, a total of nearly a thousand scrolls were found in the decade after World War II, dating from around 250 BC to 50 AD. Many were religious texts, including the oldest known biblical texts.

If you compare the Isaiah scroll with the modern text you see all of these differences

Other old manuscripts do exist, but not in such large volumes. A number of biblical texts even have many versions, offering insight into the origins of the Old Testament. Because in some places, those old biblical texts differ from what the Bible says today.

‘One of my favourite things to do, is to read the Isaiah scroll and compare it with the modern text and you see all of these differences’, says Hayes. ‘In the Isaiah scroll they use far more vowel markers, what we call the matres lectionis, whereas in the current Hebrew text, they don’t have this. And then there’s all these little mistakes.’

Mistakes

Printing an extra book wasn’t an option at the time, it had to be copied. And sometimes scribes made mistakes, or the one who was reading it to the scribe (which was faster) made a mistake. Such a copied book perhaps was copied again at a later time. So you could say that you can see the bible texts evolve in the Qumran scrolls, Hayes agrees. ‘Absolutely.’

Hayes was able to do her research thanks to the ERC-grant of 1.5 million euros received by professor Mladen Popovic of the Qumran Institute. It meant she could combine her knowledge of palaeography, or handwriting analysis, with the expertise of UG colleague Maruf Dhali on artificial intelligence. The question: who wrote those (bible) scrolls?

Using handwritings, palaeologists had previously figured out that most of these scrolls were written by different people. Yet one scribe was thought by palaeographer Ada Yardani to have as many as 54 to 90 scrolls to his name, because in all these scrolls, a complicated Hebrew letter, the lamed, was written in a very particular way. Hayes wanted to find out if Yardani’s hypothesis was true.

Digital pictures

For this she didn’t use the scrolls themselves – they had already pretty much fallen apart back in the sixties, because they were badly stored. Now they are safely locked away at the Israel Antiquities Authority, the archaeological service located in Jerusalem’s Rockefeller Museum. She was allowed to see them, in the back of the museum, ‘where the real ones are actually kept.’

You can see the bible texts evolve in the Qumran scrolls

For the actual research she worked with digital pictures of 57 of the 90 texts that could possibly be attributed to Baruch. Dhali blew them up until only the pixels of the pen strokes remained. Subsequently he entered all those manuscripts into a programme.

Using artificial intelligence, Dhali and Lambert Schomaker had previously established that the famous Isaiah text must have been scribed by two different people. So it was already clear that the scribes could approach each other’s writing style.

Interpreting the data

The analysis resulted in a pile of data. ‘It showed the distances between data points in all 57 manuscripts and every manuscript in relation to another.’ Hayes then had to try to interpret it: where did this data deviate to such an extent that you had to assume a different scribe?

This way she was already able to write off 41 manuscripts. The margin of error was too high. According to the algorithm, however, twelve others still had a 55 to 100 percent chance of being written by the same person.

It was then up to Hayes to use the old-fashioned method of palaeography to sort out the remaining manuscripts. To do this, she chose six difficult-to-write letters; the aleph, bet, he, ayin, shin and taw, and assessed them letter by letter, describing column by column objectively what she saw and whether it resembled other forms of that letter. It turned out that some deviated too much.

Eventually she concluded that Baruch had scribed ‘just’ eight manuscripts. One from the last discovered cave near Qumran, number 11, and the others from cave number 4, where the majority of all scrolls was found. The other scrolls simply differed too much from Baruch’s handwriting, even though they used the same ‘developed, ornate, curvilinear style’, as Hayes calls it.

Educating others

That the people who transcribed bible texts were merely copying them isn’t true, Hayes says. ‘Because they are involved in the transmission process of texts. They prepare texts to be read, studied and engaged by others. Also the scribes learn from their texts, they are educated by them and then they educate others. So it’s taking in the text and sharing it with others.’

The scribes learn from their texts and then they educate others

According to her, Baruch too was a scholar who was part of a group of experts, a network of people responsible for gradually changing the Bible, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Her PhD research on the oldest versions of the Bible did change her view of its origins, she says. Hayes grew up with Christianity in Australia; her sister is a pastor there. ‘It changed my view on the Bible a lot.’

Patriarchy

Women, by the way, had little business in Qumran. According to one manuscript, when the messiahs (plural) were there, women were not allowed to live in Jerusalem. They were only allowed into the city for short visits. They also had to menstruate in special camps.

‘Obviously, back in the day it was a patriarchal society,’ says Hayes, ‘which is sad.’ She moves her newborn baby to her other knee and gently taps its bottom. ‘Mind you, I sometimes think: oh man, nowadays women need to do it all! Which is great, but it’s hard.’

If it were possible, she still would have liked to meet Baruch, she confesses in her dissertation. She even wants to write a novel about his life. ‘I think I’m gonna have him as a scribe who was educating women. And something like that is why his wife gets killed and he finds himself on his own version of the “hero’s journey”. Somehow in all of that, he finds himself at Qumran.’