The inventor of the electric car

A brilliant

rascal

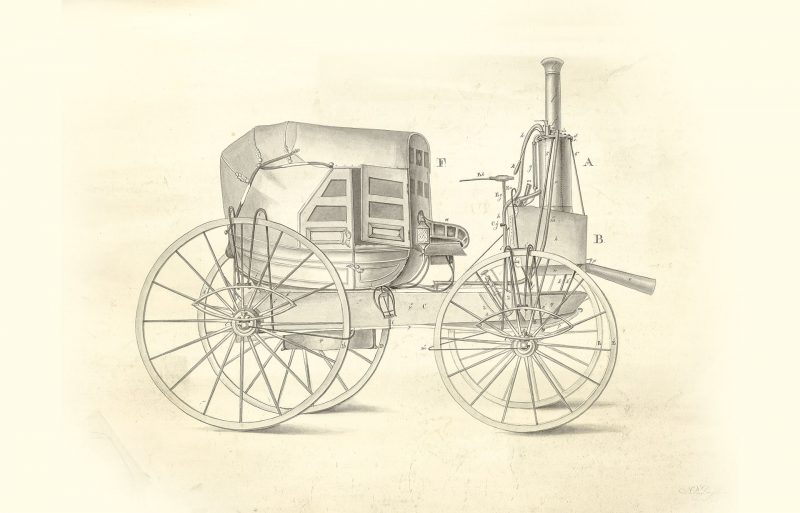

Stratingh designed and created a steam-powered wagon. And not just any wagon: it honestly looked quite a lot like a modern car. This was back in 1834, years before steam trains became a thing in the Netherlands and way before the first car, a Benz Victoria, was driving the streets of The Hague in 1896.

He also created the first electric car in the world. In 1835. Okay, so it was more a slab of wood on wheels with a battery and a motor, but it was the first time anyone used an electric motor to make something move.

Chemistry artist

He was also the first person to use chlorine to fight a pandemic, when the mysterious Groningen epidemic killed 10 percent of the city’s inhabitants in 1826. Let us not forget the light bulb. He invented one in 1830, forty-nine years before Edison did the same.

Nineteenth-century scientist Sibrandus Stratingh wasn’t just some schmo. He was, as one of his friends said, a chemistry artist. And while he’s mainly known as the ‘inventor’ of the electric car, he’s responsible for many more breakthroughs.

One thing he was particularly good at was combining new scientific insights for practical applications. ‘That’s the definition of innovation’, says Ulco Kooystra, who is receiving his PhD for his research on Stratingh.

Test drive

The UG website names him as one of the great icons of the past. But Kooystra realised there was a lack of proper research on Stratingh.

He also loved the theatricality of science; experiments that literally went bang

The only thing he could find was his obituary, written by his friend Theodorus van Swinderen, and a few newspaper articles from when he was driving his steam-powered wagon through Groningen. To be fair, it was a spectacular sight. Stratingh and his instrument maker Christopher Becker would drive it from Groningen to De Punt, a small town twenty kilometres outside the city.

Half of Groningen had come to see the test drive. It was such a big success ‘that, once it is properly finished, this carriage will not only be able to traverse stone and rock roads, but it will even be able to withstand the bumpy cobbled streets’, the Provinciale Groninger Courant wrote on March 25.

Design of the steam car with which Stratingh and his instrument maker Christopher Becker drove from Groningen to De Punt, twenty kilometres outside the city.

Inattentive

But it’s only now becoming clear how innovative Stratingh actually was, says Kooystra. He’s often painted as inattentive, bouncing from one study to the next. ‘He also enjoyed the theatricality of science; he liked experiments that literally went bang.’

‘My study shows how all his studies were connected and one led to the next. His writing was also popular. His articles were praised both in the Netherlands and internationally. He wasn’t just praised for the work he did, but also for how he managed to forge connections between things people already knew’, says Kooystra.

Stratingh was born in the village of Adorp, the son of a minister. When he was three, he went to live with his uncle, who ran a pharmacy in the city. Kooystra isn’t sure whether that’s because he was so brilliant and he would be able to get better schooling in Groningen, as his friend Van Swinderen would claim later.

Thirteen languages

‘Interestingly enough, his brother was also placed out of the home when he was very young. I wonder if there was something going on in that family. But I don’t know what.’ At any rate, young Sibrandus was a smart boy. He attended Latin school when he was eight and started the ‘academy’ when he was fourteen.

He is said to have spoken no fewer than thirteen languages. Then again, that’s another claim by Van Swinderen, says Kooystra. Considering the fact that Stratingh had letters from foreign friends translated and wrote them in his native Dutch, we should probably take it with a grain of salt.

They called it physique amusante, entertaining experiments

And yet. He did become a pharmacist, which meant he was mixing chemical substances for years. ‘In those days, a pharmacist did more than just make medication’, says Kooystra. ‘He also made fireworks.’

Physique amusante

Together with his friend Van Swinderen, Stratingh started the Natuur- en Scheikundig Genootschap (Society for Physics and Chemistry) in 1801. This group did all sorts of experiments, for instance with an electrostatic generator that Van Swinderen’s brother had bought. ‘They could generate sparks and lightning’, says Kooystra. ‘They called it physique amusante. Experiments that were actually entertaining.’ But Van Swinderen and Stratingh also used the generator for more serious experiments.

They also did experiments using the recently discovered substance of chlorine, as well as various metals. Materials that, when combined, could produce a pretty big bang. ‘Stratingh was a bit of a rascal, really.’

All these experiments paved the way for him to become a professor in 1823. They also came in handy when the Groningen epidemic broke out and no one knew why so many people were dying.

Stratingh’s car, in fact the very first electric car.

Cholera

‘Stratingh was put in charge of the effort to use chlorine to fight the disease and he even set up a small factory to make chlorine compounds.’ He used his position to do extra experiments and write a long book praising chlorine as a disinfectant. ‘As a result, the Netherlands started using chlorine during the next cholera epidemics.’

His interest in steam engines was also awakened by the society. There had been plans to build one for years, says Kooystra. In the end, Stratingh, impatient, decided to build one himself.

‘His design was well ahead of its time. English designs had the motor in the back, forcing the driver to communicate with the boilerman in the back. But Stratingh’s design had the motor in front, allowing a single person to drive and stoke the machine.’ Quite brilliant, really.

Burners

It’s incorrect that Stratingh stopped working on his invention because the steam wagon was loud and dirty, says Kooystra. ‘The government decided that his design wasn’t safe with just one driver.’ After that, the government decided to stop wasting time on cars and to invest in trains.

I read it and realised he’d created a light bulb

Kooystra doesn’t think Stratingh’s switch to experimenting with an electric car was a way of trying to improve on the steam-powered wagon. Rather, it was the next step in his research into efficient burners. ‘Back then, people analysed substances by burning them. But in order to reach higher temperatures, they needed to use ovens. However, those prevented them from showing the experiments to students.’

Stratingh was looking for a burner that would burn hot in the open air. One device he used was a so-called deflagrator, which could generate heat using a primitive battery. He also purchased one of the very first dynamos, made by French instrument builder Pixiï.

Light bulb

In 1830, Stratingh transmitted electricity through a piece of platinum wire suspended in between two electrodes inside a vacuumised bottle, which produced quite a bit of light. ‘I read that and realised that he’d created a light bulb!’ says Kooystra.

However, Stratingh didn’t pursue the experiment any further. At the time, he was also working on carbon lamps, which produced much more light. ‘I think he didn’t realise the value of his discovery because there was a better alternative to it.’

In 1834, he heard about Moritz Hermann von Jacobi building the first electric motor.

While Jacobi’s official article on it wasn’t published until a year later, Stratingh managed to build one, too. ‘I think he realised that in terms of physics, it was the opposite of the direct current generator he already had. Especially back then, it was remarkable how he immediately figured that out.’

The first

In the end, he created the car that would make Stratingh a household name.

He was indeed the first, says Kooystra. Some people claim that Hungarian inventor Ányos Jedlik was the first one in 1827, and that Strantingh’s design was simply the first one that could actually move, but Kooystra doesn’t think so.

‘He never published an article on it’, he says. ‘Jedlik talked about it, sure, but only when he was eighty. Besides, are we supposed to believe he managed it even before Jacobi built the first electric motor in 1834?’ Kooystra puts no stock in the story.

It’s a little sad that Stratingh, the brilliant inventor, innovator, and visionary, died so young, in 1841, at the height of his career. No one knows what killed him. What if he’d been able to continue his work? ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if he’d soared to even greater heights if he hadn’t died.’