Where does the UG’s art come from?

A giant molecule & revolving art

The Zernike molecule

‘It’s not particularly pretty’, says physics student Puck Planje. ‘It doesn’t really ooze intellect, either.’

‘It’s a nano-car, right?’ says maths student Ozum Turhan. ‘It clearly shows we’re at FSE, but I’m not sure I’d call it art.’

The students are talking about the giant molecule that was installed on the grassy field in front of the Energy Academy at Zernike in 2016.

The red and white piece is an enlarged version of the ‘nano four-wheel drive’, one of the molecular motors that won Groningen chemist Ben Feringa the Nobel Prize that year. You’d think it would be the university’s pride and joy.

And yet few students know what it is or why it’s there. There’s no sign explaining the ground-breaking discovery anywhere, and no one knows how it was put on the field in front of the Energy Academy.

‘I have no idea’, the Academy’s receptionist says when we ask. She refers us to area manager Kees Bulthuis, who tells us to go to Science LinX, FSE’s centre for science communication. ‘They take care of expositions and science-based art.’

No one knows how the molecule ended up on the grassy field

Unfortunately, Science LinX doesn’t have a great answer for us, either. ‘We’re not involved in this and we don’t know who’s in charge of the art’, the department says. ‘We know the molecule belongs to Ben Feringa, so perhaps his institute has more information.’

A quick internet search leads to more information. The giant molecule was an idea by the municipality, Marketing Groningen, and the UG. It started out at the Grote Markt, was moved to the Aa church, and even spent some time in front of the Academy building. But what happened to it after this?

It was moved to the Zernike campus, where people kind of forgot about it, admits UG spokesperson Elies Wempe-Kouwenhoven. ‘It was a present for Feringa originally. And we’re really glad to have it. But we’re not entirely sure who’s responsible for the thing.’

But eight years after he’d won the Nobel Prize, the molecule is placed 250 metres away from the Feringa Building that was named after him, meaning most students have no idea of its meaning.

‘Honestly, I had no idea that this won a Nobel Prize’, says maths student Nik Carnelio. ‘I just thought it was a random molecule.’

Ozum also thinks more should be done to make the piece stand out: ‘It deserves a sign that explains what it is.’

Revolving art at the Harmonie building

‘I once went all the way around to see all the different pieces’, says art history student Lia Calancea. ‘I love all the different styles.’

‘I think it’s a great idea’, says student of international relations Roos Farzanh.

Anyone entering the Faculty of Arts at the Harmonie building is sure to see the art being displayed in the revolving door at the main entrance to the building. The art itself is ‘revolving as well’; every once in a while, the space becomes available to a new artist. ‘It’s pretty much always faculty students or staff’, says Koen Drewers, who chairs the art committee at the Faculty of Arts.

Drewes is a cameraman at the university and, like most of the other people on the art committee, works at the audiovisual services department, which supports the faculty. ‘It’s an extracurricular activity, but fortunately, I’m allowed to do it during regular office hours.’

We put out a call for work and were overrun with people’s submissions

He proudly shows us a small storage room full of art pieces, mounting equipment, and tools. The corner is taken up by a giant abstract painting. ‘I have no idea who painted that’, he says. ‘I’ve made an appointment with an art historian to see if we can figure it out.’

When he founded the art committee five years ago, his first resolution was to put up new pieces in the revolving door every month. ‘It used to always be the same’, he says. ‘I wanted to change that. We put out a call for work and were overrun with people’s submissions.’

He used to have a long waiting list, but Drewes has noticed people are less enthusiastic these days. ‘The current work has been there for a few months.’

The work consists of four small, colourful paintings, displayed on similarly small easels. One of them displays an apple, while another one shows the earth as seen from space. Below is a QR code that takes you to the artist’s Instagram page. ‘In these pieces, I’m combining the contrast in value and colour, using expressionist lines and impressionist elements’, she writes.

The work belongs to first-year European cultures student Ewi Serrano Chaves. ‘I would see the display every morning’, she says. ‘But I wasn’t sure if I was ready to show my art.’

She is really happy she did, though. ‘It’s allowed me to show so many different sides of my identity’, she says. ‘It doesn’t quite force people to look at my art, but it does push them towards it.’

The responses have been positive. ‘Everyone I knew was really enthusiastic’, she says. ‘Hopefully it’ll inspire others to also work on their art.’

Hallway at the Heymans building

‘I’ve never really paid attention to the art’, says Sanne Kamps, who’s studying to be a teacher, about the art in the Heymans building. ‘I just keep walking.’

‘I never really considered it’, confesses psychology student Maximilian Gebauer.

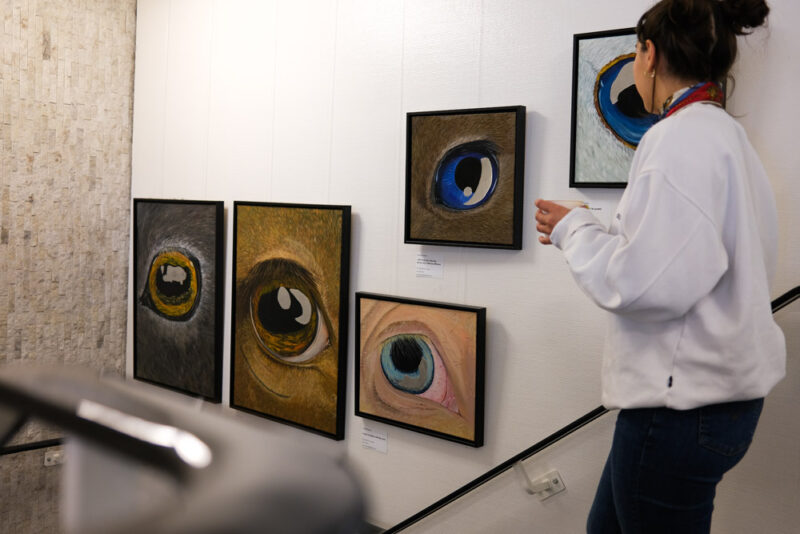

The hallway has been adorned with artwork since early April: abstract paintings or drawings that come together to form a single picture, and three large paintings of expressionist eyes above the stairs.

They were made by the clients at ATN, the Autism Team of the Northern Netherlands. They hope to bridge the gap between practice and theory. ‘Various clients wanted to showcase their artistic side and were prepared to show a vulnerable side, too’, the organisation says. ‘They’re giving these future psychologists a peek into their existence, identity, mind, and feelings.’

I never really paid attention to the art

One of the pieces was made by twenty-eight-year-old Marion Roelink. Her art – a black and white drawing – hangs right in front of the entrance. It shows an alleyway with a cartoonish character walking a giant insect on a leash. ‘People always ask me if that’s supposed to be me’, says Marion. ‘But I just draw whatever I’m thinking of.’

She enjoys observing things, she says. ‘I just felt like drawing this. I’m curious to know what people think.’

Maximilian reconsiders the piece. ‘Now that I’ve looked at it for a bit longer, I kind of like it’, he says. ‘But the rest of the art in the building is a little depressing. Maybe we can put up things that are a bit more daring?’