Creating power out of weeds

The spark of nature

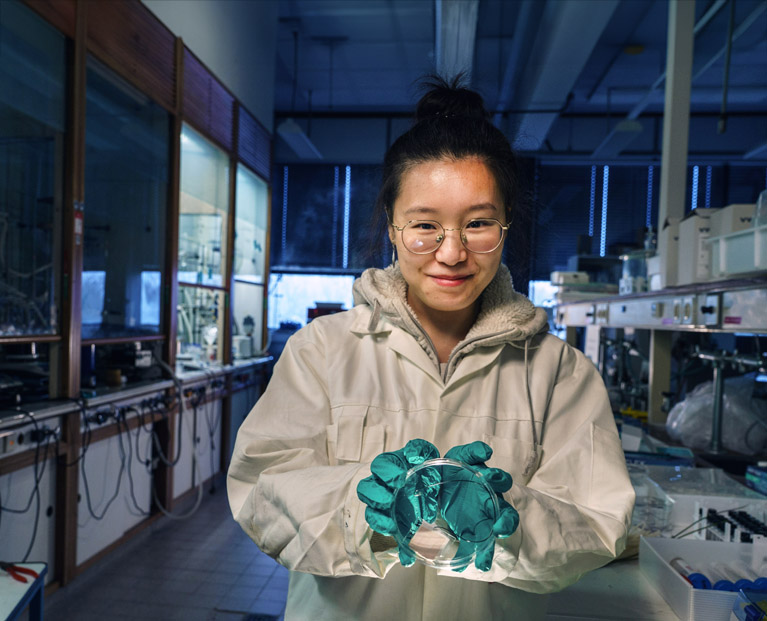

When Qi Chen arrived at her lab three years ago on a quiet morning, a surprise awaited her. A few days earlier, she had been extracting material from a soft rush plant to see how she could make useful new structures out of it. But she spilled some of the solution of the grass-like weed over a sheet of aluminium foil.

Now, she noticed something unusual had happened: the spill had solidified into a thin film. ‘Oh my god’, she thought. ‘This is exactly what I need.’

Spongy structure

Since the start of her PhD in macromolecular chemistry, Qi Chen had been trying to find ways to produce electricity from nature. Some animals, like electric eels and rays, or the star-nosed mole, have special organs that produce electricity. Plants can also create energy. Chen had tried to achieve this by harvesting the tiny power outputs released by a culture of bacteria.

Oh my god, this is exactly what I need

She worked with a common wetland plant called soft rush, also known as Juncus effusus, which contains a spongy material. This is how it is able to float above water and transport plenty of air to its roots.

Chen had learned about the plant by coincidence. ‘I was sitting in a field near Zernike Campus with some friends at the time and mentioned that I needed a foam-like structure for my research. And one of my friends, who was peeling the skin off some weeds, gave me the plant, saying that it looked exactly like what I needed. We were just joking’, Chen says, ‘but I thought: maybe he’s right?’

Perfect housing

Chen saw that the core of the soft rush plant did in fact make for the perfect environment for her electricity-producing microbes; even more so than any costly lab-designed structure she could come up with.

However, after some time, she abandoned the project. Since her lab was meant for research into polymer chemistry, it didn’t necessarily have the right equipment to create good conditions for the microbes. ‘It was also quite tricky to work with them, and ultimately they were just not managing to create enough power’, she says.

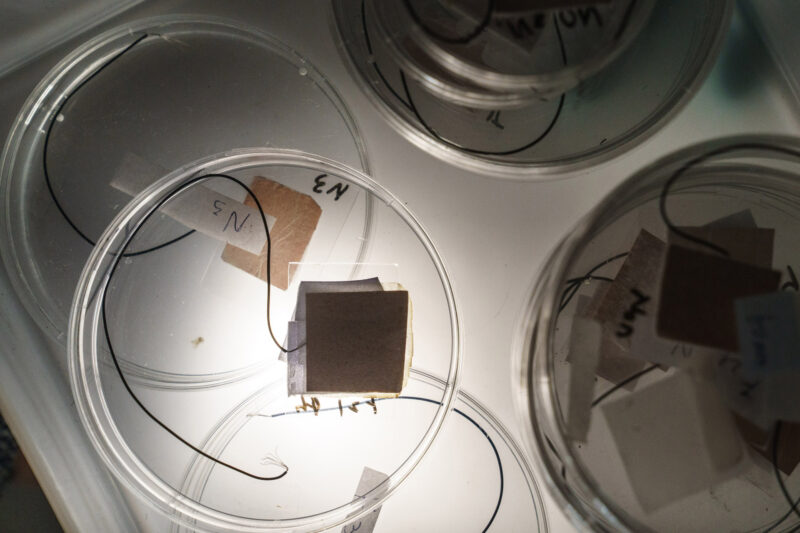

Still, the foam inside the soft rush had piqued her interest and she wanted to know what sort of structures – especially two-dimensional ones – she could make out of it. The tricky part had been to find a way to get the material into such a fine layer, but now, with that lucky spill, she had found it.

Static electricity

When she examined the film for the first time, she was amazed. It was extremely lightweight, highly porous, and had a rough surface. ‘It looked just like a stack of star-shaped bubbles’, Chen says. As it turns out, this makes it ideal for creating static electricity.

And just like that, making power was back on the menu. When the layers of soft rush film slide against each other, the friction between them generates small jolts of static electricity. Just like the electricity we create when we put on a warm woolly sweater.

Why use so much energy for something that only needs a little bit of power?

Ever since then, she’s been working on the next step: finding ways to actually use these tiny plant-based generators. One application, which she developed alongside colleagues Dina Maniar, Wenjian Li, and Feng Yan, is to use them as motion sensors. ‘You can detect any contact between the layers simply by measuring the power output.’

Many usages

The concept is simple, but the sensors can be quite useful. They can be integrated into shoes to gather data about the way people walk, for example. This could help understand how people can recover from injuries to their knees, feet, or legs. The sensors could also detect whether someone who lives alone took a nasty tumble and is in need of help.

There are other possibilities too, from healthcare to wearable technology, although Chen prefers not to go into too much detail. After all, research is still underway. However, she predicts that the strips can end up powering all sorts of small devices and even be used in batteries.

And since they are bio-based, biodegradable and quite lightweight, they are sustainable too. That makes them an alternative for many small devices made with 3D printing or other techniques involving hazardous chemicals or high energy costs. ‘Why would we use so much energy and resources for something that only needs a little bit of power? It’s a waste!’ Chen says. ‘That’s why this film is so good, because it’s easy to make and it’s all natural.’

And even better, it’s really, really cheap. ‘It’s a weed, something that’s not welcome in a garden or in agriculture’, she says. ‘So it’s a nuisance for most people, but a really great resource for me.’

Only time will tell how many more applications Chen will find for the soft rush plant. But one thing is certain: whenever she hits a wall, she can always turn to nature for inspiration. ‘There’s so many great discoveries taken directly from there’, she says. ‘I hope our research can help people appreciate the beauty of nature.’