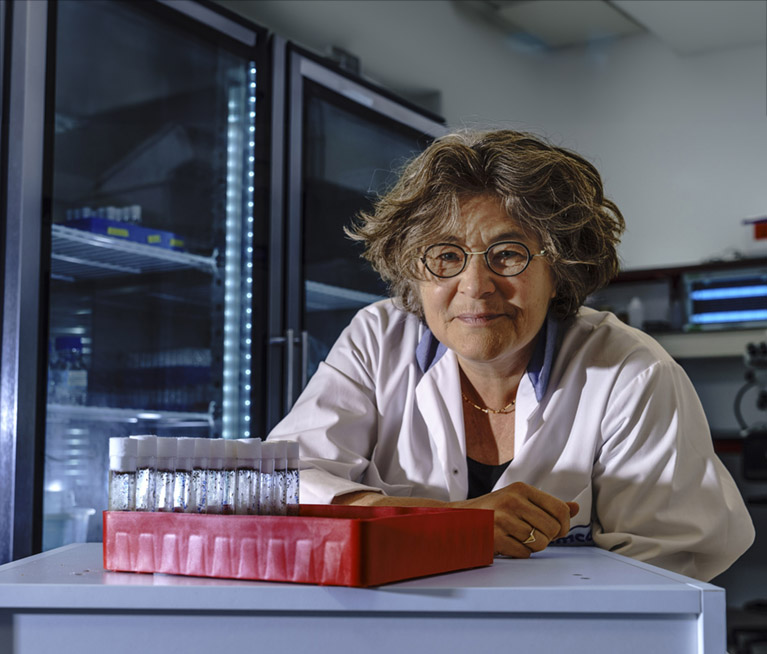

ThebreakthroughOdy Sibon

A remarkable control test

‘We should probably look into this further’, UMCG professor of molecular biology thought when a colleague from South Africa she was hosting told her about the possible role that intestinal bacteria played in treating PKAN, a serious brain disease. It turned out to be just the thing.

PKAN is a nasty disease. ‘People are born healthy, but the first symptoms pop up after approximately two years’, says Sibon. ‘Patients start falling down and their ability to speak declines. Most people with PKAN end up in a wheelchair before they’re even ten years old. Most of them die around fifteen years.’ There currently is no effective treatment for the disease,

which is caused by a metabolic error. Under normal circumstances, the body converts vitamin B5, a molecule that can be found in eggs, vegetables, and nuts, into coenzyme A, which is needed to provide cells with energy. But this process doesn’t work in people with PKAN. An enzyme that’s supposed to ensure the conversion has a malfunction.

Fruit flies

Sibon’s search for a treatment didn’t involve any research on people or, as is common in the medical world, on mice. Instead, she used fruit flies. ‘PKAN is a neurodegenerative disease’, she says. In other words, the older a patient is, the worse their symptoms get.

‘That means we need mainly older test subjects’, she adds. ‘It takes mice two years to grow old, but fruit flies only take three weeks. Besides, working with mice requires a lot of paperwork because of the ethical implications of that kind of research, which is completely justified, by the way. But it’s easier with flies.’

While flies do differ quite a bit from human beings, that’s of no concerns in this stage of the research. ‘The disease is caused by a malfunction in the DNA’, say Sibon. ‘It’s easy to replicate that malfunction in the DNA of fruit flies. It means they won’t live for eighty days like healthy flies. Instead, they’ll live for twenty days and won’t be as good at climbing or flying.’

Pantetheine

To figure out where it went wrong, Sibon followed the route that that vitamin B5 makes while turning into coenzyme A in the fruit flies. ‘We kept adding a different intermediate from the route to the flies’ food’, says Sibon. ‘We noticed that giving them the intermediate 4 phosphopantetheine helped. With that, they did produce coenzyme A.’

It wasn’t quite a working solution, however: it’s a difficult substance to create and it’s very expensive.

However, pantetheine, a similar molecule that doesn’t appear in the route from vitamin B5 to coenzyme A, is easier to make. They use the molecule as a control test: if everything is working as it should, using pantetheine will not result in the creation of coenzyme A.

At least, that’s what they thought. But to Sibon’s surprise, the control test was positive: against all expectations, the fruit flies were using the pantetheine to make coenzyme A.

Antibiotics

What was happening here? Everyone was baffled, says Sibon. ‘But then I remembered a conversation I had with South African professor Erick Strauss. He was on sabbatical in the Netherlands in 2015 and he told me that bacteria were really good at living of off pantetheine.’

Could it be the bacteria in the flies’ intestines taking over one of the crucial steps in the process towards coenzyme A? To find this out, Sibon attempted to deactivate the intestinal bacteria by giving the flies antibiotics. It worked: the flies without gut bacteria were no longer able to transform pantetheine into coenzyme A, thus confirming the link between those bacteria and the production of coenzyme A.

A follow-up study will have to prove whether administering pantetheine to people will have the same effect. ‘If it does, we might develop pantetheine into an affordable treatment for PKAN and similar diseases.’