Happy at the UMCG

Particle accelerator has a future again

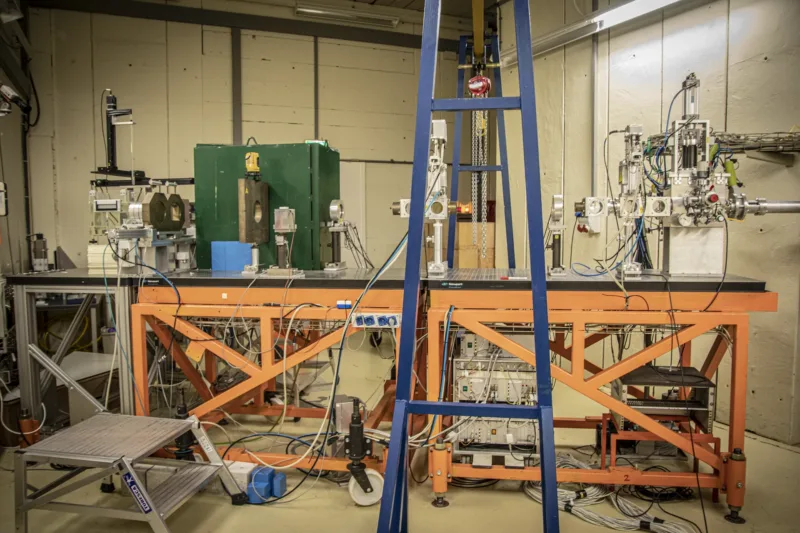

Researcher Emil Rehberg and his colleague, both hailing from Belgian nuclear research institute SCK, are standing in a lab at Zernike campus, fighting to stay awake. ‘It’s been a long night’, the researcher says, grinning. They slept for a few hours during the day, but now they’re back for round two with the AGOR particle accelerator. They haven’t been able to see much of the town.

‘Research moments like these are few and far between’, says Rehberg, ‘so we’re spending all the time we have as best we can.’ You can’t just turn the accelerator on and off: it takes at least a few hours to start up.

The Belgians will be back next year, says SCK research leader Kavin Tabury. ‘We’ll be irradiating beating artificial heart tissue on a chip. It’s really cool.’

It’s good that the researchers will be back, because AGOR needs clients to break even, let alone turn a profit.

Cyclotron

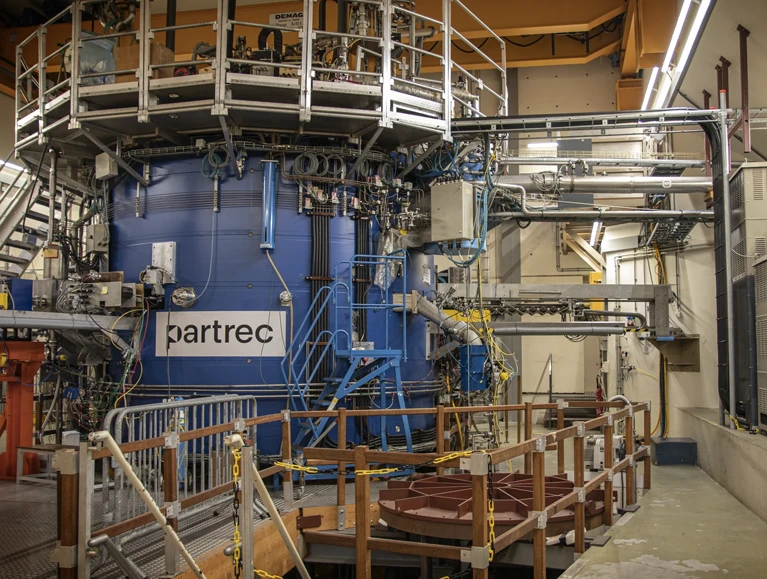

Profit isn’t the only thing that the centre isn’t turning. In fact, nothing much turns at AGOR, says Harry Kiewiet, who’s been working for thirty-three years at this institute, which started off as the KVI (Kernfysisch Versneller Instituut), later became the KVI-CART (Center for Advanced Radiation Technology), and is now called PARTREC (Particle Therapy Research Center).

Sure, the atomic particles take a few hundred laps around the particle accelerator before they’re fired at half the speed of light through tubes and past magnets in a test set-up. But the machine itself, also known as a cyclotron, a blue, round, metres-high colossal machine weighing four hundred tonnes housed in a concrete bunker with walls that are 2.5 metres thick, does not move.

It’s nice to work for an organisation that’s willing to buckle down

The UMCG took over the entire institute, including AGOR (short for Accélérateur Groningen-Orsay) from the UG on January 1, 2020. At that time, it had a deficit of four hundred thousand euros. The UMCG’s job was to make up for a decade of overdue maintenance, hire a full contingency of staff, market the cyclotron, and ensure it was budget neutral.

With the work force sorted, the UMCG is currently investing in maintenance. At the same time, managing director Henk Heidekamp is working hard on marketing the particle accelerator, focusing on marketing plans, branding, stands at conferences, and client visits. Together with professor of proton therapy Stefan Both, he just showed a new potential client around. They won’t tell us who it was, but the pair is enthusiastic about the future of PARTREC.

Extraordinary capabilities

As heavy as AGOR is, it’s also incredibly flexible. While there are 1,500 cyclotrons in the world, only two others can do what AGOR can: fire both heavy and light particles, and both protons, photons, and ions.

The proton therapy centre at the UMCG has one too, but it can only fire protons at a relatively high speed, Kiewiet explains. Besides that, researchers are always the last in line for beamtime: patients come first. Because of that, they also have to be more careful. ‘We can’t accidentally unplug a cable if the next person who needs the machine is a patient.’

But it’s the extraordinary capabilities of AGOR that made the Belgians come to Groningen. However, PARTREC needs more researchers to come by, because the cyclotron goes unused too often. In fact, it’s only in use 30 percent of the time. Heidekamp sees an opportunity to break even.

At the start of 2020, they were given five years to do so, but the pandemic meant everything was shut down for two years, says Both, frustrated. On top of that, the war in Ukraine led to a worldwide shortage of helium which the accelerator’s super colliders need, because the helium factory was in the war zone.

But things are back on track. In addition to researchers from ESA, CERN, and commercial clients from the aviation and aerospace industries, the centre also hosts scholarship researchers, such as nuclear physicist Julia Even, who is looking for new particles in the periodic table. There are sixteen research applications still pending, says Both. So yes, it’s going quite well, the two say.

Decommissioned

But the cyclotron has nearly been decommissioned several times. In 2004, when the FOM, a foundation that promoted fundamental physics research, which later was made a part of research financier NWO, decided to stop doing nuclear physics research. The UG immediately went looking for other income, and for a million euros a year, it got to help German research institute GSI build its own accelerator.

It’s always about money

In 2013, when the last bit of FOM money came in, the board of directors turned to instrument manufacturers, who they thought were wizards with resources. Perhaps the KVI could be turned into a high-tech instrument manufacturing plant? Market research said no.

The only thing that was left at the time was the uncertain advent of a proton centre at the UMCG and the resulting research. According to insiders, Groningen was the only logical choice for such a centre, precisely because of the knowledge present at the KVI. ‘The data that showed that proton therapy would be a good idea in the Netherlands came from research that was done here’, says Both.

The KVI became KVI-CART, the focus on nuclear physics research dwindled into non-existence, and the astronomers made due with a retired professor, but the proton therapy centre was a certainty, and the research into proton radiation blossomed. So much so even that the board of directors, who wanted to get rid of it, decided the institute was better off with the UMCG than the Faculty of Science and Engineering.

UMCG

During a meeting in January of 2019 ‘the news came as a blow’, says technician Oscar Kuiken. Financial manager Jan de Jeu had been a little too blunt in bringing it, he feels. ‘He simply said that they would find out if they could move us to the UMCG and that if they couldn’t, they’d find us a different job and just put an end to the whole business.’

In the end, the decision was made that September, after the board made the promise earlier that year that no one would be forced to resign.

Now, three years later, Kuiken is happy with the way the transition to the UMCG went: ‘It’s much nicer to work for an organisation that is willing to buckle down and make investments and go for great results than it is for one that makes you feel like you have to walk on eggshells because they might pull the plug at any minute.’

Cultural change

Hans Langendijk, professor of radiotherapy and boss of the PARTREC staff, wasn’t too worried about the future in 2019. ‘I’ve faced hotter fires’, he says, laughing. The fact that it took so long to reach a decision came down to money, according to him. ‘It’s always about money.’

If we were to pass on the energy costs, all our clients would run away

PARTREC moving to the UMCG did entail a cultural change. ‘It’s become more commercialised’, says director Heidekamp. ‘There’s no such thing as a free lunch’, he says several times. That means everyone needs to log their hours and help recruit potential clients.

In April, they’re attending a large European conference, where they’ll have their own stand. Langendijk has high expectations: ‘Especially if we send a few well-connected people who are experts in what we can do. That’ll make it a lot easier. It’s all about contacts and networking.’

Energy bills

However, there is one big uncertainty: who’s going to pay the particle accelerator’s energy bill, which has risen exponentially? ‘If we were to pass on those charges, all our clients would run away’, says Heidekamp. He thinks the board will have to pick up the slack.

The UMCG, in turn, turned to the UG. But the university has already had to dip into its savings to pay its own multimillion-euro energy bill, Hans Biemans told the university council last month. ‘Everyone’s asking themselves who’s going to pay the energy bill’, Langendijk says.

‘If we can rent out 80 percent of the beamtime, we’ll be alright, even with the current energy prices’, Heidekamp says, optimistic. ‘And there’s no reason to think we won’t succeed.’

However, those high energy bills means finding new clients is of utmost importance, says Langendijk: ‘We have our work cut out for us.’