How a robotic falcon is saving airplanes

The secret of dancing birds

Have you ever seen a murmuration of starlings in the fall? Did you see them dancing – hundreds, thousands of birds – moving in mesmerising synchronicity at ultra high velocity? The way they move from shape to shape in just a matter of seconds is like ballet dancers performing a meticulously prepared artistic routine. Only the birds didn’t train for months and months.

So how do they do it? How do they fly like one, without disruptions?

That is exactly what biologist Marina Papadopoulou has been trying to find out. For four years, she has been researching bird flocks in order to understand the patterns they collectively create, specifically when they encounter dangerous situations. To do this, she created computer simulations of such flocks.

Distracted

‘I never really paid attention to bird flocks before, but now I can’t take my eyes off them’, she says. ‘If I’m talking to someone and I see a flock of birds passing by, I immediately shift my attention towards them. I like to joke with my friends that this is the way I will die, being distracted by a flock of birds while cycling.’

This is the way I’ll die, being distracted by a flock of birds

However, her research is about more than just understanding the beauty of the birds. When birds come near airports, they run the risk of hitting airplanes. These bird strikes can create technical problems for the aircraft when the birds get sucked into the rotors of the engines.

This happens quite often. According to the American Federal Aviation Administration, there have been 227,005 bird strikes involving civil aircraft between 1990 and 2019 in the US alone. In that same span of twenty-nine years, there have been 292 human fatalities caused by bird strikes globally, as well as 327 human injuries.

Fake alarm calls

Knowing how and why bird flocks move is essential to bring those numbers down, because the ways airports currently try to prevent bird strikes are not very effective, Papadopoulou says. ‘They might use fake alarm calls, or kites. The problem is that birds often get used to those practices.’ She wants to find a solution that is more natural to the birds, by using their natural instincts.

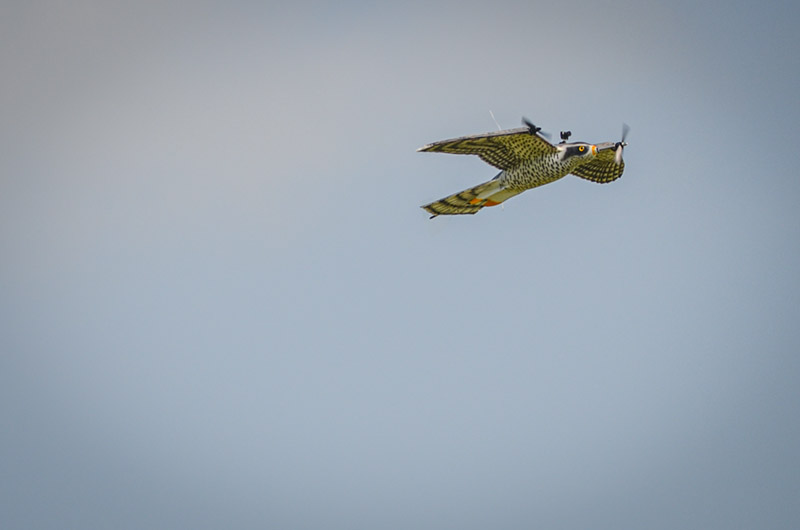

In order to do that, Papadopoulou and her colleagues have been using a robotic, remotely controlled falcon to drive the birds away from the crowded airspace of airports. ‘It’s just like a shepherd dog would try to lead the sheep in a particular direction.’

The falcon creates a ‘dangerous situation’ which makes the flocks move. It seems to do its job well: ‘We haven’t seen any habituation effects so far, since birds are not able to distinguish it from a real falcon. They treat it as a real threat.’

But more importantly, Papadopoulou can use the data the falcon gathered and transfer it to functional simulation models to really get to the heart of what the birds are doing.

Labour intensive

At this point, we really do not know yet what is happening within these flocks. Researchers have to study bird flocks in their natural habitats, which makes the process longer and more labour intensive than with other animals. ‘It’s not easy to put GPS tags on hundreds of birds, not knowing if you are even going to get your data back.’

It’s not easy to put GPS tags on hundreds of birds

‘With fish, for example, you can take them, put them in a water tank in the laboratory, and study them, record them and collect a large number of useful positional data. But with birds you can’t do that. Remember, these flocks, depending on the species, can be as big as a hundred thousand individuals.’

The models created by using the robotic falcon provide a solution. ‘They allow me to analyse patterns of behaviour and why they occur’, Papadopoulou says.

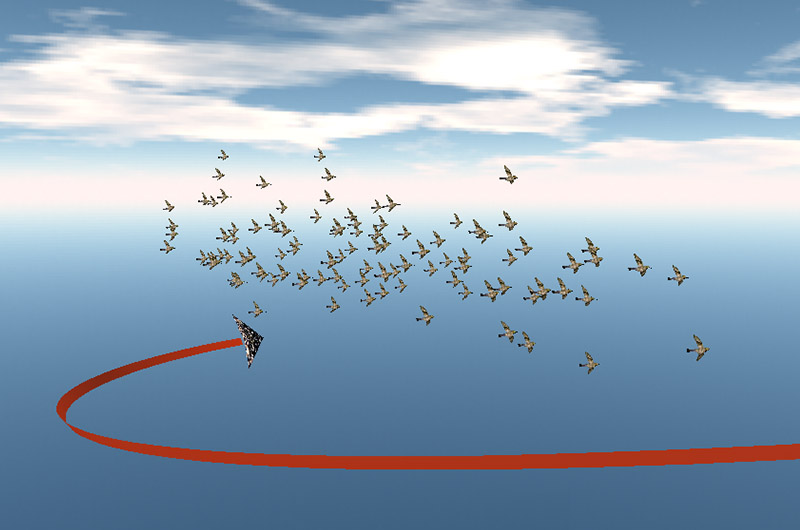

Being in a large group gives birds a higher chance of surviving. ‘The predator gets confused by that many individuals, so focusing on one particular individual becomes much harder’, she explains.

Danger

When a flock encounters danger, though, they respond differently. Starlings may create many different patterns, whereas pigeons usually create only two: they either turn away together or they split into two different groups. ‘Both of these variations have one very simple explanation’, Papadopoulou says. ‘One individual decides to turn, and what happens then depends on how many others will follow.’

Experience can play a role in how birds are positioned in the group

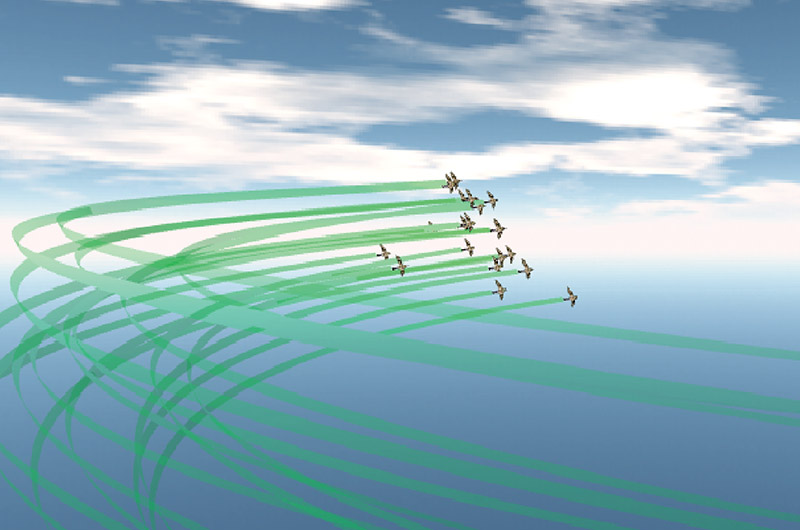

Another important factor for the pattern created is simple flight aerodynamics, Papadopoulou found. ‘Whenever an individual is losing altitude while performing a manoeuvre, the shape of the flock will be affected’, she explains. The field of view of a bird plays into it as well. They will usually follow the movements of their neighbours, but when those birds turn, they’re not able to do the same, which means they are more likely to split away from the group.

Papadopoulou feels more study is needed to find out what influence the individual birds have on the collective. Right now, researchers study the flocks as a whole and each bird in it as an exact copy of their neighbours. Of course, that’s not the case in real life.

Social relationships

‘Physical traits such as age and weight can influence the speed and position of the bird within the flock’, she says. ‘But non-physical traits such as experience can also play a role.’

Less experienced individuals are usually more susceptible to imitating their neighbours while flying together, Papadopoulou feels. ‘Lastly, social relationships within the flock are also an important factor in shaping the group, as birds sometimes tend to stay closer to their mate than to the rest of the flock.’

The researcher definitely wants to continue studying collective behaviour in different species of animals, she says. ‘I just started my postdoc on a project that has as an end goal to focus on flock robotics. The aim is to analyse data of different species such as baboons, fish, goats, and also birds, in order to better understand individual heterogeneity, and how similar individuals are within a group.’