Retirement? What’s that? #7Doekele Stavenga (79)

‘I don’t know how to slack off’

‘Does the name professor De Waard ring any bells?’ biophysics professor Doekele Stavenga asks. ‘He was an absolute giant in the field of physics. They organise an annual lecture in his honour in the auditorium of the Academy building.’ Even when De Waard was declining mentally, Stavenga still visited him regularly.

‘It still hurts talking about it’, says Stavenga. ‘Such great abilities being destroyed.’ The retired professor realises how lucky he is. ‘Not everyone has access to a laboratory or is still doing research when they’re eighty.’

Being important is fun for a while, but at some point you’ve seen all the tricks and all the fights

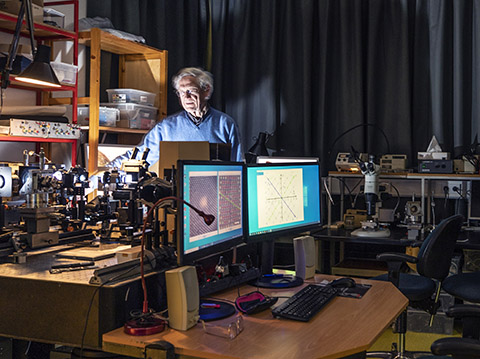

Thanks to a grant from the United States that he shares with five other research groups in Europe, Stavenga is free as a bird. The grant doesn’t pay him, however. ‘I can live off my pension.’ He uses a wide range of microscopes and spectrophotometers to study the colours and reflection of butterfly wings and bird feathers. He also studies how butterflies and flies see flowers.

Quit

In addition to his research, which has spanned the length of his nearly sixty-year career, he also headed up the physics department, sat on various committees, and was involved in education. When he turned sixty, he decided to quit most of his work.

He has no regrets. ‘The field of education became encumbered by management and keeping people in check. Being important is fun for a while, but at some point you’ve seen all the tricks and all the fights. Teaching a class is strenuous. You can’t decide your own speed. But you can in research.’

Watching these fumbling students turn into creative researchers keeps me young

In fact, he considers doing research his duty. ‘In this day and age, people are encouraged to think only of themselves. But I think we should aim to contribute to society. I do that by publishing extensively, as well as by assessing articles and grant proposals every week, for Nature and Science, among others.’ He knows university staff is overworked. ‘So if I can lighten their load by doing those assessments for them, I can help.’

Promotion rights

He also regularly supervised PhD candidates, but he’s since passed that job on to his colleagues. He became a guest researcher when he turned seventy, which means he no longer has the right to confer doctoral degrees. ‘That’s fine with me. It’s about the PhD candidates, not the professor. I simply enjoy working with students and PhD candidates, making new discoveries together. Watching these fumbling students turn into creative researchers keeps me young.’

Stavenga isn’t the only person of retirement age at his department. His technical assistant Hein Leertouwer, who started at the university in the seventies, is eighty-four years old. His wife has passed away, Leertouwer says. ‘But my job means I still have a lot of social contact on an academic level.’

Slack off

It may not be much, but Leertouwer spends at least three half days in the lab. For eight years after his retirement, Stavenga was at the lab on a daily basis, and he still goes three days a week. At first his lab was still located in the physics department, now he’s joined the biologists at the Linnaeusborg.

‘Whether I’ll scale it back to two days mainly depends on my wife’, says Stavenga. ‘She knows how much I love this, but she occasionally tells me to slack off for a day. But I don’t know how.’ Stavenga will keep going as long as he’s appreciated. ‘People in the field still appreciate me, but as soon as they start asking me if perhaps it’s time, I’m leaving.’

Retirement? What’s that?

Series | These scientists don’t know how to quit