‘It’s very clear our country doesn’t want us back’

Chinese students stranded in Groningen

‘It’s very clear our country doesn’t want us back’

‘I’ve seen ticket prices as high as ten thousand euros. That’s practically the same as refusing us entry.’ Chinese UG student Sam Hao is angry. Many of his fellow students want to go back to their home country, but they can’t afford to.

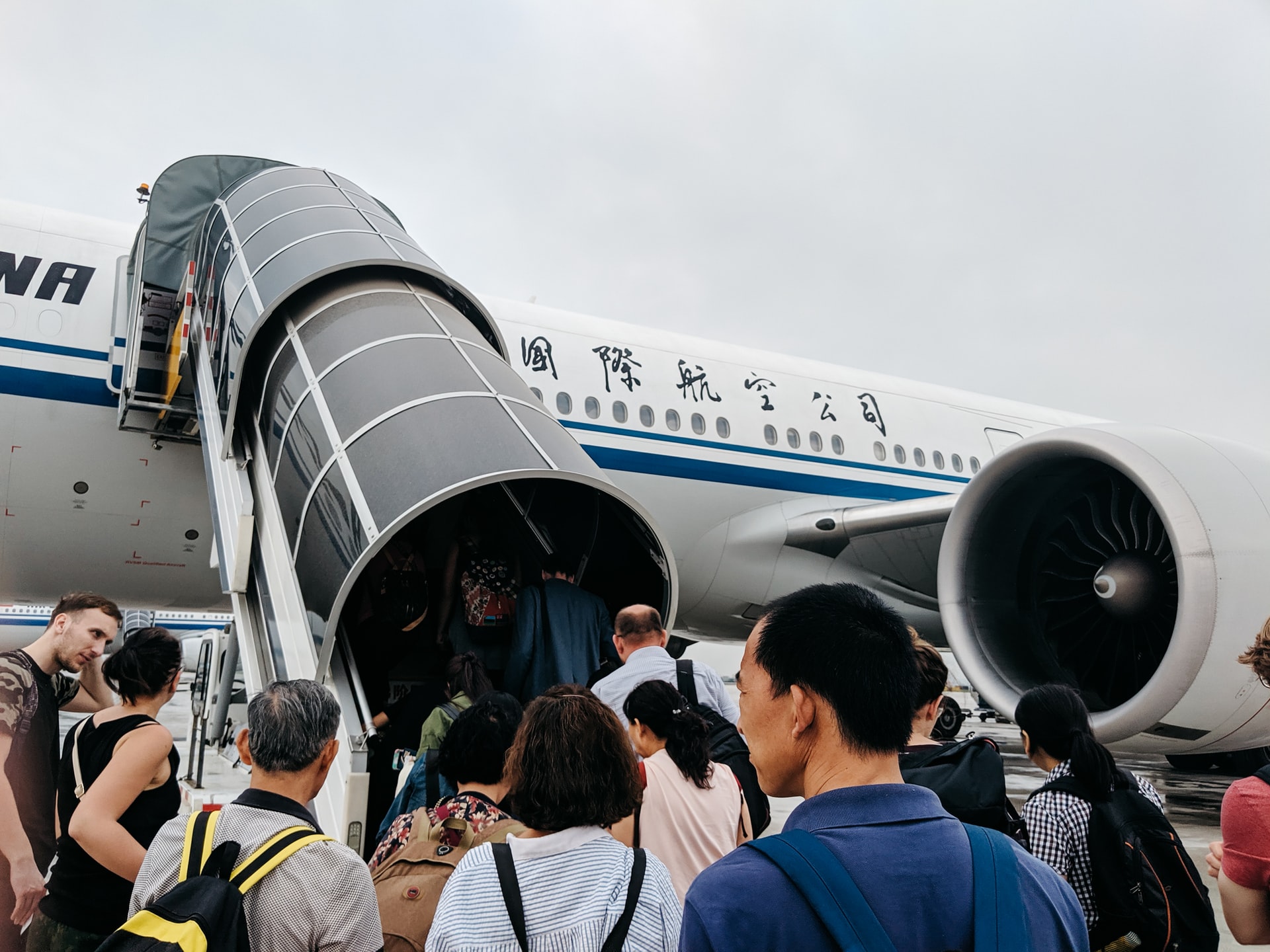

China doesn’t openly block its citizens abroad from returning during the corona crisis, but it has capped the number of flights to the country, to the same effect. It’s been dubbed the ‘five-one policy’: one flight via one route by one airline, per country, per week. As a result, ticket prices have skyrocketed.

‘It’s shameful for the government to do this’, says Chen Yin, another UG student. ‘There are so many Chinese people overseas, the government can’t be excused for trying to block them from coming home.’

Disappointed and upset

Sam and Chen feel abandoned by their government. ‘It’s made me very angry, disappointed, upset’, says Chen. ‘It stings me when I look around Groningen and see Dutch people socialising. I had plans with friends in China and now I don’t know when I’ll be allowed by my own country to go home.’

Because they fear backlash from the Chinese community, both Sam and Chen use a pseudonym for this article. It’s risky being critical of Chinese policy, says Sam, who read the threats in a student WeChat group following an UKrant article on the Hong Kong protests in November. ‘You’re seen as a traitor, but we don’t want to be the enemy.’

I don’t know when I’ll be allowed by my own country to go home

Still, they’ve noticed that’s how they’re viewed in China. ‘They say we’re selfish for wanting to go home’, says Chen. Comments she’s read on the internet are very hostile. People are scared that returning countrymen will bring the coronavirus with them, and because they are high-risk, they should pay the higher ticket fee.

Even if they do manage to enter China, they have to stay in a hotel for fourteen days and cover those costs themselves. ‘It’s very clear they don’t want us back’, says Sam.

He himself has no plans to return as long as Xi Jinping is president, but he feels for the other Chinese that are stuck abroad. Of the more than eight hundred Chinese students in Groningen, only a hundred have made it home.

Face masks

For those that are still here, the Chinese embassy in the Netherlands has provided face masks. Chen picked them up, even though she says she’d ‘rather be able to afford to go home than be given a thousand masks’.

Sam didn’t pick up the masks. He believes it’s like sticking a band-aid on a bullet wound. ‘It’s useless. It’s an alternative to offering affordable plane tickets, but it sends a message that we’d better find a way to survive by ourselves in a foreign country.’

The Chinese student association in Groningen, ACSSG, volunteered to help distribute the masks among students in April. But Sam didn’t trust the Google form he had to use to sign up. ‘Maybe I’m too sensitive,’ he says, ‘but it asked for all your personal info, like your student and Chinese ID numbers and your address. I immediately think they were spying.’

We’d better find a way to survive by ourselves

It’s just a feeling, he says, but in China everything is somehow related to the government, even a student association. Plus, he’d already ordered his own two hundred face masks from China directly, and donated half of them to the UMCG.

Considerate

Ruiqi Shi, the president of ACSSG, acknowledges that the five-one policy has been very inconvenient for the Chinese students in Groningen. ‘A lot of them want to go home, but they can’t afford to.’ It’s also causing problems with rent and visas, both for students who can’t leave the Netherlands, as well as those who now aren’t able to return to Groningen. But blaming the government? That’s a step too far.

‘It’s a special time, and we should all be more considerate,’ says Shi. ‘The government has to make decisions for reasons we don’t really know. We shouldn’t complain about things we don’t totally understand.’

There are other factors at play as well, he says. Shi has heard about Chinese students in America who can’t get direct flights to China because of the ongoing tensions between the two countries. ‘So they have to fly via Amsterdam, which also increases the ticket demand.’ That further hikes up the price.

Lonely

Chen wants to wait until the price of a ticket drops to a thousand euros. But that might mean she’ll be waiting until October, because the five-one policy will probably last until then.

She’s tried to talk about her situation in Groningen with friends in China, but they don’t really believe her. They think Chinese living abroad have nothing to complain about. ‘But I just want to go home’, says Chen. ‘I feel lonely.’